"If everyone has to abide by the same rules, then maybe we will finally make progress in making the world food system more sustainable," says Frederik Claasen, Head of Policy at the NGO Solidaridad. He sees the introduction of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive within Europe as a positive development. On one condition: that the 200 million small farmers for whom Solidaridad is working are not excluded. Without ‘fair data’, fair trade is an illusion. And therein lies a huge problem.

Solidaridad is an international civil society organization with more than 50 years of experience in developing solutions to make communities more resilient. From its early years, its focus has been on making trade fair and supporting small-scale farmers. A few years ago, the organization realized that by now data and standards determine the balance of power in the value chain. Fair trade needs fair data. That is why Solidaridad is working on its own formats with which small-scale farmers can develop into an equal partner in the sustainable food chain.

The CSRD regulations in force since the beginning of this year, can be a catalyst in this, said Frederik Claasen, Solidaridad's head of policy, during the Digital Food webinar ‘Fair Farm Data and CSRD’. But it can also lead to further exclusion of small-scale farmers, and Solidaridad wants to avoid that at all costs. For now, the CSRD reporting rules apply to approximately 50,000 retail and processing companies. These have to specify their scope 3 emissions policy, i.e. provide insight into the emissions in their supply chains.

Claasen shows that 200 million small farmers produce 75% of all cocoa, 70% of all coffee and tea, 75% of all cotton, 40% of all sugarcane and 30% of all palm oil. For their efforts, however, they get paid only a fraction (about 3%) of what consumers pay in stores for finished products. This is because a handful of large companies control all the commodity flows: commodity traders, food corporations and large retail companies.

From consumer and voluntarily to government and compulsory

Solidaridad wants to promote transparency and international cooperation throughout the value chain. Initially, Solidaridad did so based on the idea that if only consumers had insight into what was behind a product, they would make a difference. Solidaridad became the basis for three sustainability labels: Fairtrade, Max Havelaar and UTZ (now Rainforest Alliance). When that proved insufficient, the focus shifted to the large companies in the value chain. Solidaridad put corporate social responsibility on their agenda and got public-private partnerships up and running. Unfortunately, constantly having to find new sponsorship funds proved ineffective. The next step was Round Tables (such as for Palm Oil and Soy) and other multi-stakeholder initiatives. For small farmers, it still offered too little help. Claasen therefore sees new, mandatory sustainability standards and agreements such as the European CSRD as a possible good step forward.

'Small farmers have no data'

"But then comes the big problem," says Claasen. "Becoming part of the data ecosystem and the data economy is imperative, it becomes a license to operate. However, the small farmers have no data, no access to the Internet, and no platforms."

Seven years ago, Solidaridad realized that "data" could potentially be the most efficient driver of sustainability in the value chain. However, you then need to develop one or more business models that also make it attractive for farmers to share their data so that you don't have to continually ask them to provide data.

Solidaridad took the lead - "our USP is that we know exactly what to do to connect, because we know the farmer so well," smiles Claasen - and developed a number of 'first mile' applications, which allow farmers to easily share their data while ensuring that the data is also well structured. "The underlying principles are simple," says Claasen, "the data is and remains the farmer's, and sharing it is done in such a way that interoperability is guaranteed."

Business models

During the webinar, Claasen showed two examples of Fair Farm Data applications, such as the Indian SoliCloud platform that uses various apps - from soil analysis to hyperlocal meteorological stations - to relieve farmers by automating data collection:

screenshot SoliCloud, Frederik Claasen

screenshot SoliCloud, Frederik Claasen

The South African Z'wardy system, which rewards farmers through a practical incentive system, is an example of a way for remote farmers to share their data and works on the basis of a concrete earning system. All a farmer has to do is register on his phone, then use the obtained ID card (a QR code) to collect points. You get those points when using apps, and if you get enough points you can exchange them for clothes, manure, seeds, training and even to have them delivered. It is also possible through Z'wardy to have risk analyses done or to receive climate change advice. If you apply the provided advice, you can earn points.

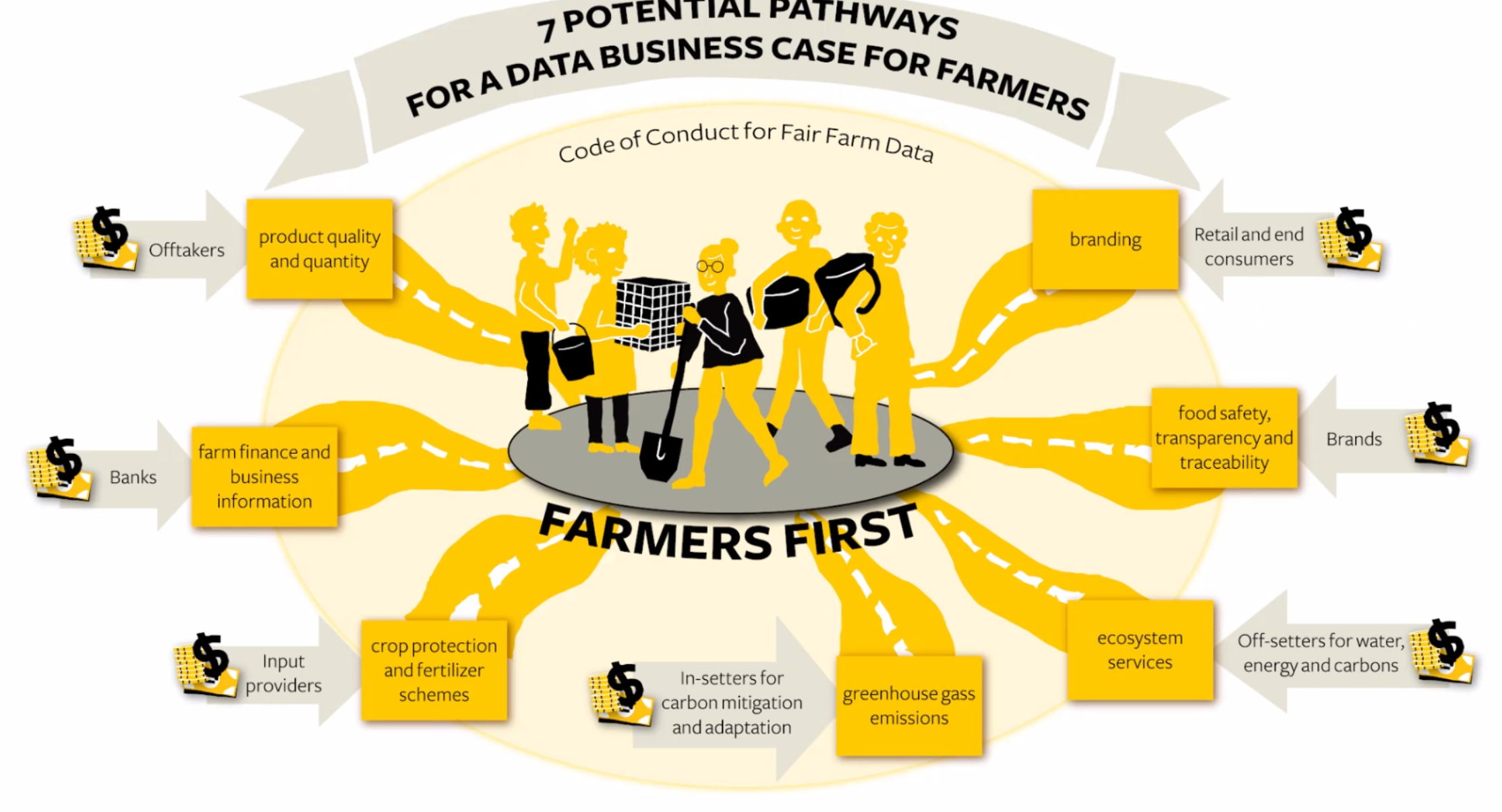

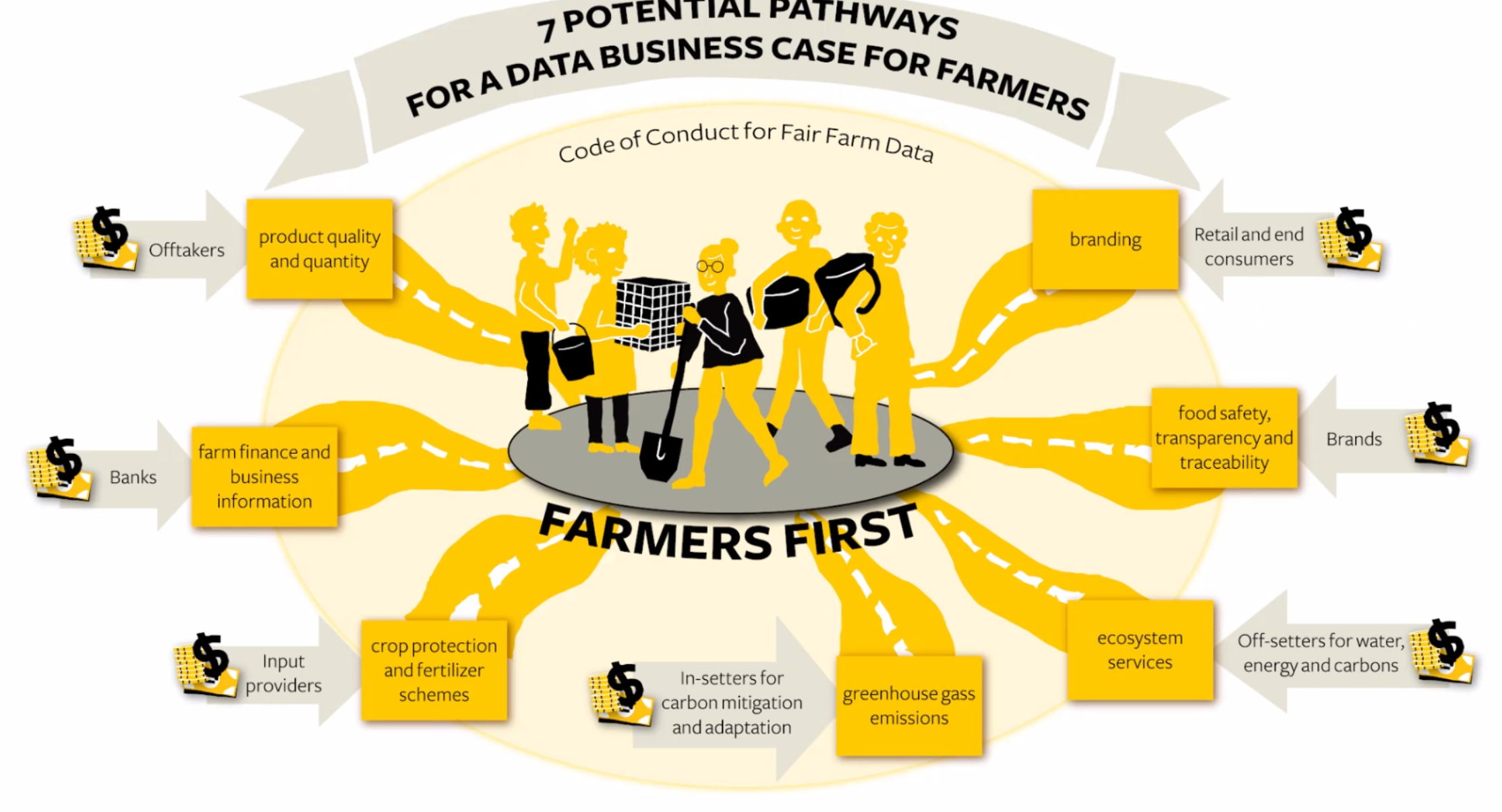

Solidaridad has developed seven business models, i.e., 'strategic pathways', with which farmers can earn money by making their data available. Rabobank's - not entirely unproblematic - carbon bank is one of them. Planting trees and trading their rights creates an additional cash flow. Other 'earning opportunities' include better access to financing opportunities or receiving compensation for ecosystem services.

screenshot Potential Data Business Cases, Frederik Claasen

screenshot Potential Data Business Cases, Frederik Claasen

Discussion

In the lively discussion following the presentation, two things stand out. When asked about the additional earnings that the business models bring to farmers, Claasen says this is still being investigated further, in cooperation with Maastricht University. "Additional earnings of 10 to 25 percent of income are possible," Claasen says. For example, in the cocoa chain, tracking and tracing from plantation to store, combined with the story Solidaridad can tell, and the premium the farmer gets for sharing his data, can yield an additional 10% on top of the price the farmer normally gets. "That's not enough to escape poverty, the pieces of land are too small for that, but it helps.”

The big challenge that remains in the whole effort to resolve the balance of power is determining what part of the data is "pre-competitive”. Large companies will never share competitively sensitive data. For some companies, such as Cargill, data sharing is non-negotiable anyway. But, says Claasen, if you consult with farmers - because after all, they are the masters of their own data and will have to understand what happens to their data - and make clear which data is important to all parties, you stay ahead of the competition phase. Then everyone, including the companies, has an interest in having reliable and transparent data that benefits the entire supply chain.

The CSRD regulations in force since the beginning of this year, can be a catalyst in this, said Frederik Claasen, Solidaridad's head of policy, during the Digital Food webinar ‘Fair Farm Data and CSRD’. But it can also lead to further exclusion of small-scale farmers, and Solidaridad wants to avoid that at all costs. For now, the CSRD reporting rules apply to approximately 50,000 retail and processing companies. These have to specify their scope 3 emissions policy, i.e. provide insight into the emissions in their supply chains.

200 million small farmers produce 75% of all cocoa, 70% of all coffee and tea, 75% of all cotton, 40% of all sugar cane and 30% of all palm oil. For their efforts, however, they get paid only a fraction (about 3%) of what consumers pay in storesThat's not easy when hundreds of millions of small-scale farmers have neither the money nor the techniques to come up with the data needed to do so. But they are the first link in the supply chains. From the very beginning, Solidaridad has been working on behalf of small-scale farmers precisely because they do not have a voice, but they produce most of the important and, for us, valuable agricultural goods.

Claasen shows that 200 million small farmers produce 75% of all cocoa, 70% of all coffee and tea, 75% of all cotton, 40% of all sugarcane and 30% of all palm oil. For their efforts, however, they get paid only a fraction (about 3%) of what consumers pay in stores for finished products. This is because a handful of large companies control all the commodity flows: commodity traders, food corporations and large retail companies.

From consumer and voluntarily to government and compulsory

Solidaridad wants to promote transparency and international cooperation throughout the value chain. Initially, Solidaridad did so based on the idea that if only consumers had insight into what was behind a product, they would make a difference. Solidaridad became the basis for three sustainability labels: Fairtrade, Max Havelaar and UTZ (now Rainforest Alliance). When that proved insufficient, the focus shifted to the large companies in the value chain. Solidaridad put corporate social responsibility on their agenda and got public-private partnerships up and running. Unfortunately, constantly having to find new sponsorship funds proved ineffective. The next step was Round Tables (such as for Palm Oil and Soy) and other multi-stakeholder initiatives. For small farmers, it still offered too little help. Claasen therefore sees new, mandatory sustainability standards and agreements such as the European CSRD as a possible good step forward.

'Small farmers have no data'

"But then comes the big problem," says Claasen. "Becoming part of the data ecosystem and the data economy is imperative, it becomes a license to operate. However, the small farmers have no data, no access to the Internet, and no platforms."

Seven years ago, Solidaridad realized that "data" could potentially be the most efficient driver of sustainability in the value chain. However, you then need to develop one or more business models that also make it attractive for farmers to share their data so that you don't have to continually ask them to provide data.

Solidaridad took the lead - "our USP is that we know exactly what to do to connect, because we know the farmer so well," smiles Claasen - and developed a number of 'first mile' applications, which allow farmers to easily share their data while ensuring that the data is also well structured. "The underlying principles are simple," says Claasen, "the data is and remains the farmer's, and sharing it is done in such a way that interoperability is guaranteed."

Business models

During the webinar, Claasen showed two examples of Fair Farm Data applications, such as the Indian SoliCloud platform that uses various apps - from soil analysis to hyperlocal meteorological stations - to relieve farmers by automating data collection:

screenshot SoliCloud, Frederik Claasen

screenshot SoliCloud, Frederik ClaasenThe South African Z'wardy system, which rewards farmers through a practical incentive system, is an example of a way for remote farmers to share their data and works on the basis of a concrete earning system. All a farmer has to do is register on his phone, then use the obtained ID card (a QR code) to collect points. You get those points when using apps, and if you get enough points you can exchange them for clothes, manure, seeds, training and even to have them delivered. It is also possible through Z'wardy to have risk analyses done or to receive climate change advice. If you apply the provided advice, you can earn points.

Solidaridad has developed seven business models, i.e., 'strategic pathways', with which farmers can earn money by making their data available. Rabobank's - not entirely unproblematic - carbon bank is one of them. Planting trees and trading their rights creates an additional cash flow. Other 'earning opportunities' include better access to financing opportunities or receiving compensation for ecosystem services.

screenshot Potential Data Business Cases, Frederik Claasen

screenshot Potential Data Business Cases, Frederik ClaasenDiscussion

In the lively discussion following the presentation, two things stand out. When asked about the additional earnings that the business models bring to farmers, Claasen says this is still being investigated further, in cooperation with Maastricht University. "Additional earnings of 10 to 25 percent of income are possible," Claasen says. For example, in the cocoa chain, tracking and tracing from plantation to store, combined with the story Solidaridad can tell, and the premium the farmer gets for sharing his data, can yield an additional 10% on top of the price the farmer normally gets. "That's not enough to escape poverty, the pieces of land are too small for that, but it helps.”

The big challenge that remains in the whole effort to resolve the balance of power is determining what part of the data is "pre-competitive”. Large companies will never share competitively sensitive data. For some companies, such as Cargill, data sharing is non-negotiable anyway. But, says Claasen, if you consult with farmers - because after all, they are the masters of their own data and will have to understand what happens to their data - and make clear which data is important to all parties, you stay ahead of the competition phase. Then everyone, including the companies, has an interest in having reliable and transparent data that benefits the entire supply chain.

Recently, we wrote about CSRD and the emerging power of accounting rules. Since the government is presumably going to leave those accounting rules to the market, and the big accounting firms see a revenue model in that, arbitrariness arises. It seems that the EU is nevertheless going to give accountants room to set up standard and data models through large firms. Solidaridad's initiative is an attempt to build logical and physically correct standards from the other side. Because agriculture has by far the greatest influence on land usage, leaching, and water use within the food chain, it would seem natural to start with the farmer. Transparency is both the means for farmers to charge costs to the chain necessary to operate more sustainably and at the same time the guarantee that they are not abusing their position at the beginning of the chain.

Related

It would be interesting to hear Claasen's opinion on a similar (at least in my opinion) data-driven initiative by other Dutch organisations: AgriGRADE. By the look of it, it seems to offer more development perspectives than the Fair Farm Data program, because it takes into account the fact that farmers are organised into cooperatives, thereby strengthening their position.

Another indication of this non-organisational approach by Solidaridad is Claasen's statement that Solidaridad has been working on behalf of small-scale farmers precisely "because they do not have a voice...". This is simply not true: small-scale farmer are organised in multiple ways and at multiple geographical levels, and (try to) make their voice heard by private companies, governments and oher stakeholders.

Regrettably, it has happen all too often in the past that non-membership-based organisations and NGO's say that they act 'on behalf of farmers' when they do not have that mandate. The only ones that have that authority and legitimacy are membership-based organisations like farmers' unions, cooperatives, producer associations and similar entities. Apparently it is necessary to repeat this time and again.

Anyway, and leaving aside the relative merits of the two initiatives above, it is also sad to see that there are two Dutch initiatives to begin with, both purporting to improve the position of small farmers in value chains. That does not sound like efficiency.

As said, I hope that that Frederik Claasen can react to these comments!