Standards, labels, or ISO standards boring? Far from it. The digitalization of agriculture and the food industry is moving so fast that food makers and processors from large to small can no longer escape standards. They define what is good and in doing so create the world of tomorrow. That’s why everyone should care.

Digitization creates transparency on how food is grown, processed, and sold. Standards determine what we call ‘good’. Products must comply with these standards because processors, manufacturers and retail companies want to prove to you via a QR or other code that they are combating climate change, are not damaging the environment and biodiversity, and are dealing ethically with fellow humans and animals.

Thus, the world of tomorrow is being created at a rapid pace. Those who do not participate are excluded because they cannot show how they contribute to a better world. But that’s not all. Those who do not participate in thinking about or questioning the standards are leaving the world of tomorrow to others.

In the EU, for example, it must be decided whether nuclear power is sustainable. Whether biomass is sustainable seems to be politically off the decision-making agenda. Scientifically, this is surprising, because biomass power plants are now fuelled by trees from North America and the Baltic that have been specially felled for energy production, and possibly even by shredded trees from Dutch forests. This is definitely unsustainable. The outcome of political considerations and choices determines the type of standards that are created.

No one has an interest in the common good

No supplying company or maker of standards has an interest in resolving this confusing situation. After all, having their own standard for their own business buyers with their own consumers is the goal. The general interest is not guarded by anyone, not even, as the examples of organic farming and biomass as 'sustainable' energy show, by the government itself. This inhibits the creativity of entrepreneurs, their ability to innovate and their ability to do business with multiple buyers. This runs counter to the public interest but is how the digitalization of food is now beginning.

Anyone who realizes this will therefore be pleased to hear a different tune during the webinar “Global Governance by a No-Body”. Major players from the world of standards said they want to work together to build a universal taxonomy and harmonize standards to allow different standards and the development of new ones to peacefully coexist. After a discussion on the need for harmonization and a universal taxonomy, Kristian Möller of GlobalG.A.P., Mirjam Karmiggelt of GS1, Marjan de Bock-Smit of Impact Buying, Hans de Gier of Syncforce, and Han Brouwers of Solidaridad found each other in the desire to work together to ensure that this taxonomy and harmonization come about.

Möller was crystal clear as early as 2020 about the challenge posed by divergent standards. "We talk about harmonizing data, but we also need to talk about harmonizing standards." He said this because there are already many different ecological, climate and ethical standards for food, and more continue to be added. If we do nothing, it reduces the ability of farmers and horticulturists to do business with different buyers. After all, they must meet the requirements of a standard, logo or a buyer and can no longer meet those of another if the latter prefers to use a different standard.

Open table

The aforementioned standard setters and application makers for standard users want to do something about this confusion by setting up an open table at which they can democratically determine in front of society how they can cooperate on so-called interoperability - making terms and the standards in which they are composed interchangeable - to enable creative entrepreneurship and innovation.

For that to happen, a critical mass of companies using the standards must want to cooperate. The second condition is that those companies cooperate in the global public interest. As a third condition, the data must remain the property of the companies from the front to the back of the chain that generated that data. They determine with whom they share it and on what conditions those parties may use their data. After all, standard setters realize that they are only users of data that belongs to others. They are the access to information that, after processing by third parties, including themselves, can have a lot of value. That value and the way to deal with it must remain with the person who generates the data.

With those choices, the intentions and rules of the game are set. Gathering the critical mass of companies to get it on the wagon may not be as big a step as we currently think. With that, developing interoperability with a permanently democratic and publicly monitored openness comes closer.

It may sound incredibly boring but is incredibly exciting. I don't want to hide the fact that the teams at Foodlog and Agrifoodnetworks are proud to host the conversation! We hope to take next steps in 2022.

Thus, the world of tomorrow is being created at a rapid pace. Those who do not participate are excluded because they cannot show how they contribute to a better world. But that’s not all. Those who do not participate in thinking about or questioning the standards are leaving the world of tomorrow to others.

In the EU, for example, it must be decided whether nuclear power is sustainable. Whether biomass is sustainable seems to be politically off the decision-making agenda. Scientifically, this is surprising, because biomass power plants are now fuelled by trees from North America and the Baltic that have been specially felled for energy production, and possibly even by shredded trees from Dutch forests. This is definitely unsustainable. The outcome of political considerations and choices determines the type of standards that are created.

There will be a brake on the creativity of entrepreneurs, their ability to innovate and their opportunities to do business with multiple buyers. That goes against the public interest but is how the digitization of food is starting nowLet’s consider a second example. Is European biodiversity best served by far-reaching organic farming or by standards that carefully measure the environmental impact of nature-saving agriculture? The scientifically correct answer is - the latter. Yet Europe does not opt for the latter politically, even though it would benefit biodiversity – which is the reason why the European Commission chooses organic. That is why other standards will eventually develop. Half-baked, sensible, and contradictory choices will eventually translate into the many standards used by companies throughout the food chain.

No one has an interest in the common good

No supplying company or maker of standards has an interest in resolving this confusing situation. After all, having their own standard for their own business buyers with their own consumers is the goal. The general interest is not guarded by anyone, not even, as the examples of organic farming and biomass as 'sustainable' energy show, by the government itself. This inhibits the creativity of entrepreneurs, their ability to innovate and their ability to do business with multiple buyers. This runs counter to the public interest but is how the digitalization of food is now beginning.

Anyone who realizes this will therefore be pleased to hear a different tune during the webinar “Global Governance by a No-Body”. Major players from the world of standards said they want to work together to build a universal taxonomy and harmonize standards to allow different standards and the development of new ones to peacefully coexist. After a discussion on the need for harmonization and a universal taxonomy, Kristian Möller of GlobalG.A.P., Mirjam Karmiggelt of GS1, Marjan de Bock-Smit of Impact Buying, Hans de Gier of Syncforce, and Han Brouwers of Solidaridad found each other in the desire to work together to ensure that this taxonomy and harmonization come about.

Möller was crystal clear as early as 2020 about the challenge posed by divergent standards. "We talk about harmonizing data, but we also need to talk about harmonizing standards." He said this because there are already many different ecological, climate and ethical standards for food, and more continue to be added. If we do nothing, it reduces the ability of farmers and horticulturists to do business with different buyers. After all, they must meet the requirements of a standard, logo or a buyer and can no longer meet those of another if the latter prefers to use a different standard.

The aforementioned standard setters and application makers for standard users want to set up an open table at which they can democratically decide, in front of the international community, how to work together on interoperability. That may sound incredibly boring, but it is incredibly excitingImagine a tomato grower who has three major buyers who all have slightly different standards. How can he choose? In all cases, he will lose 2 customers. Moreover, this raises fundamental questions. The tomato, bell pepper or cucumber grower who, according to the EU, grows sustainably on energy from biomass, commits a crime against nature, according to activists fighting for a sustainable world. The European Commission does not want to hear about it.

Open table

The aforementioned standard setters and application makers for standard users want to do something about this confusion by setting up an open table at which they can democratically determine in front of society how they can cooperate on so-called interoperability - making terms and the standards in which they are composed interchangeable - to enable creative entrepreneurship and innovation.

For that to happen, a critical mass of companies using the standards must want to cooperate. The second condition is that those companies cooperate in the global public interest. As a third condition, the data must remain the property of the companies from the front to the back of the chain that generated that data. They determine with whom they share it and on what conditions those parties may use their data. After all, standard setters realize that they are only users of data that belongs to others. They are the access to information that, after processing by third parties, including themselves, can have a lot of value. That value and the way to deal with it must remain with the person who generates the data.

With those choices, the intentions and rules of the game are set. Gathering the critical mass of companies to get it on the wagon may not be as big a step as we currently think. With that, developing interoperability with a permanently democratic and publicly monitored openness comes closer.

It may sound incredibly boring but is incredibly exciting. I don't want to hide the fact that the teams at Foodlog and Agrifoodnetworks are proud to host the conversation! We hope to take next steps in 2022.

Thinking about interoperability bears similarities to the now heated debate about our digital identity that has flared up further after Covid and the G2 policy. Recently it was announced that the introduction of the Corona QR-code in the Netherlands, has earned Dutch ministers Grapperhaus (Justice) and De Jonge (Health) an unflattering distinction as privacy violators. Follow the Money published an extensive report last weekend, which should show that the major digital players are all out to capture our behaviour in data. The goal is to be able to analyse it and manipulate our digitalized selves to our heart's content. Depending on the demands and standards in society, they can either include us or exclude us from social intercourse. We become trapped in a world that is now called the digital twin of reality. According to the French liberal thinker Gaspard Koening in his La fin de l'individu, we even lose our identity. The same can happen to our relationship with food and the conviction from which we choose what to eat. This has far-reaching consequences because food production has a major impact on our environment and fellow beings.

De lobby voor een coronapas wordt aangevoerd door de 'digital identity industry'. Een gedifferentieerd landschap met grote en kleine spelers - maar een voorkeur voor blockchain wordt steeds meer duidelijk. Wat betekent dat? Maatschappelijk debat gewenst. https://t.co/9HWTX6HzXV

— Jannes van Roermund (@JannesvanRoermu) December 11, 2021

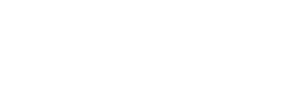

Photo credits: Standards are Great! Standardization is a really bad idea, Paul Downey

Related