AgriFoodNetworks kicked off the Digital Food Series, focusing on the theme of connecting data, technology, and strategy, and to connect people, ideas, and regions. In the first digital chat of the series, moderator Tiffany Tsui chats with panelists Paul Buisman (Moba), Kristian Möller (GlobalG.A.P.), Hans de Gier (SyncForce), and Dick Veerman (Foodlog) to discuss the challenges ahead in the world of digital food.

“Agrifood networks are very interconnected, but are also very fragmented", says Tsui right form the start. Stakeholders from various parts of the food system from all over the globe, including government, academia and specific industries (e.g. seed and egg) joined the first chat. Connecting their living apart together has unmatched value. In a number of polls the organisers tested the perception of the audience as a whole.

AgriFoodNetworks: The global open space between institutions

AgriFoodNetworks is modelled after the Dutch website Foodlog. It is intended to become the same “rare open space” to discuss and engage in conversations “without one person who has the power of authority", explains Foodlog's founder Dick Veerman. On Foodlog everyone is allowed to speak. As long as the participants try to be factual and rational, express and dig for their true feelings and respect one another, there is an open and meaningful discussion.

The value of this kind of open space is crucial in the quickly digitising world of food, Veerman says. Acting as a disruptor, digital technology is so rapidly changing the food system, society needs to decide where it wants it to go. But politics and governments based on typical western democratic political debate won't be fast enough. Digital technology is leap frogging ahead, creating an abyss between practice and law makers. "Before we notice, we'll end up with the equivalents of Facebook and Google in the world of food and find ourselves and governments complaining about it".

Just like Foodlog, AgriFoodNetworks is a place to discuss and assess what is going on and to try to define the kind of future we want, as an open people's parliament influencing media and politics. Veerman, who was originally trained as a political philosopher, considers that a quintessential element in modern society. “Law making government is always behind developments in society", he says. "Digital technology is developing so rapidly that government can hardly catch up anymore". That lays a huge responsibility on the shoulders of the private sector, as it'll have to develop the rules of the new game in the public interest, as well as its own. The private sector cannot do without government, because it needs institutions to ‘keep the game.’ “We create an open space for consumers, businesses, academics, NGO's and regular law makers to tap in and be a kind of global democracy”, Veerman says. At the same time, he intends AgriFoodNetworks to be an open space where business, ideas, and people from all over the globe can meet, connect and create new value while being closely in touch with the wants and needs of real people.

Moba: putting 70% of your eggs in one automated basket

Paul Buisman is product management director at Moba, the world's premier egg packing machine maker. Moba’s machines pack, sort, and process over 1 billion eggs a day - that’s over 70% of the automated egg industry market share.

Buisman says companies like his will only survive if they get "on the digital wagon”. He believes that there is no alternative to becoming a part of the world of digital food, and “the winners of tomorrow are the ones that step in today.” However, this doesn’t necessarily entail a complete repositioning of the roles of all actors. Instead of parties adopting new roles, they just have to digitally supplement their existing roles. For example, his machines notice what hens lay best in what climate conditions, as they can automatically monitor the product of one billion of them everyday. That's over 300 billion eggs a year. This kind of information is valuable to all in the food chain as it can be used to improve, for example, animal welfare, the level of production and feed efficiency.

Worldwide, around 3.5 billion eggs are produced a day. Out of that, 1.3 billion of them are handled automatically. This means the majority of eggs are still the product of backyard farming. 2,2 billion eggs a day are still sold or exchanged "in a little basket or paper bag”, says Buisman. A large part of the back yard volume is expected to be industrialised rather soon and may eventually be processed by Moba machines.

Processing already over 300 billion eggs per year, Moba realised the significance and value of the data the company can easily collect and redistribute. If partners preceding Moba in the chain all add their data, the egg and the processes that created it, will be digitally mirrored. That offers all kinds of information to create new value throughout the whole egg chain.

Moba's approach to data collection is a 3 step procedure.

1. Monitor day to day key performance indicators (KPI’s) to get an overall view of production.

2. Improve performance and efficiency with the ability to compare production results across a network of Moba customers.

3. Chain integration to build in traceability and certification using collected data.

“A packing station gets eggs from many different farms", Buisman says. "We plot quality in a cloud and we have an automatic algorithm that shows you right away how the eggs are doing, without any physical analysis. This gives you an immediate view on farms that aren’t performing.” The data collected after step 1 is split into private and anonymous data once it’s in the cloud. Hence, privacy and data ownership are protected, but anonymous data can still be used to build a network for users for step 2. Buisman points out that while step 1 and 2 are live already, Moba is still working on step 3.

Moba is currently working on developing “Egg Chain”, a complete track and trace system. With Egg Chain, the simple scanning of a unique product code will tell consumers exactly where their eggs came from or tell Moba customers where their eggs went. The potential for new value creation with regard to improving targeted distribution specificity and efficiency is huge. “We are actually a measurement instrument in the whole production chain", Buisman states stressing the potential for improvement.

Buisman particularly points to the importance of establishing connections between all players in their domains of the food system, even if they seem specific or niche. “How do we interconnect information from different niches? We are in a small niche. Even in our niche there are manufacturers of equipment for building farms who have their own ecosystems and measurement systems." Only the link between the variety of till now unconnected systems takes the value.” Companies like Moba are the logical knot to collect all data before them in the food chain. Their equivalents in the farming world are Lely, the Dutch dairy machine maker at farm level, and Bühler, the Swiss milling machine maker. They could be the next Facebook or Google of food. But none of them intend to do so. Buisman says he isn't even tempted. He wants to serve his customers by helping them to improve their processes and ways of doing business and creating value. In an interview on AgriFoodNetworks, Gijs Scholman from Lely made the exact same statement. Lely doesn't trade data or use it to build power, but instead distributes new knowledge to its web of business partners to better serve their consumers.

GlobalG.A.P.: setting the standard for Good Agricultural Practices

GlobalG.A.P’s Kristian Möller thinks data governance and setting standards in a digitised food world need to be on the priorities' agenda. The initials G.A.P. stand for ‘good agricultural practices’.

Möller's worldwide operating standard setting organisation “started in the area of standard setting when governments weren’t ready. It was actually private sector supply chains that needed standards and efficiency. Industry got together to develop new standards for this sector.” Möller, who is a farmer’s son and entered the industry during the mad cow disease outbreak at the turn of the century, stresses the need to balance traceability and transparency while equally distributing power to all parties involved.

When it comes to industry standards, Möller says, “we talk about data harmonisation, but we also need to talk about standards harmonisation. There’s organic standards, Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance. You have all these different standards organisations.” There are so many standards already that it can be hard to collaborate between them. That’s why in 2014, a group of standard owners signed the Declaration of Abu Dhabi for global food security. “This group of organisations decided we needed to start thinking and rethinking how we share data.”

Three pillars are at the center of the declaration:

1. A common set of practices

2. A farm ID - a system for uniquely identifying every farm that is recognised by all stakeholders

3. Reporting - a mechanism for securing the commitment network sharing of supply chain partners

GlobalG.A.P. introduced farm assurance data exchange, or FAX, a disruptive technology to connect, validate and share data in the supply chain. The organisation first began testing FAX with tech companies to see how it plays out practically. FAX puts an emphasis on bilateral business relationships with service providers and customers. Through research and development, the goal is to come up with the best available technology for the exchange and aggregation of agriculture data.

Möller states the role he hopes GlobalG.A.P., allying with farmers, can play in the data sharing process. “When it comes to data and data sharing, I don’t want to be the Silicon Valley based company who has the power to misuse data. GlobalG.A.P. wants to be the custodian where farmers will share their data. Farmers trust us, because they have governance on us. When the data is being shared with others outside of our agreement, they trust us to negotiate on their behalf so that their data aren’t misused. We sit at the table, but we are not the chair and we don’t claim to be the table owner itself. We just want to be sitting on the table with our stakeholders on an equal basis and have an open discussion so that we can build trust among parties.”

The question remains open: what's the nature of a table that nobody owns or chairs? And who keeps the rules of this 'no-body's' super-governance or sanctions those breaching them?

DataPorts: making autonomous data transfer “as easy as email”

Hans de Gier, CEO of SyncForce and the speaker of Digital Chat #2: Bye Manpower, Hello Machines and Value. SyncForce's mission is to improve data sharing both within company and between companies and their partners. This allows for a far more efficient flow of information between suppliers, business partners, and customers that isn't bound by standards.

DataPorts is an initiative of the Consumer Goods Forum (CGF), a network of globally operating companies and organisations that together try to tackle social and environmental sustainability, health & well-being, food safety, and digitisation at a pre-competitive level. The DataPorts concept and the technology to make it come true is inspired by a business need. Commercial organisations want to prove they offer products and services in the interest of society's common goals. In order to stay in business they need the consumer's engagement. That's why being transparent is the name of their game in digitised food markets. "That requires heightened collaboration and 'intelligent value networks'", De Gier says. He believes that “that's almost impossible to have if we don’t have collaboration and digitisation.”

Companies today need systems that aren't just good for business; they also need to be good for wellbeing and the planet. Product success parameters form a 'goodness paradox', says De Gier. Consumers tend to have many distinct or even conflicting ideas of goodness, as do other parties involved.“Everything has to be driven by data in order to standardise efficiency and quality". As de Gier puts it, “the foundation for an intelligent value network is a connected, data driven value network." In practice, however, it can result in a complex, expensive, low quality set of tools and procedures as competitors will try to set and impose their standards. Huge interoperability issues lurk just around the corner. De Gier jokes that there are probably “more standards than companies”.

CGF member Spar imagined replacing category management with intelligent shelves. The shelf asks itself: ‘How much space do I have? What is the weather projection like and how reliable is it? What type of consumer is in the store? What types of products will I need?’ And then it would start sourcing. De Gier stresses that in order to be widely adopted, DataPorts must be low cost, have a low entry barrier, utilise flexible solutioning, grant freedom of choice to users, adopt a global and easy discovery model, and be based on P2P exchange regardless of industry or standard.

Currently, DataPorts are being tested in pilot environments with select companies. Expansion is on the horizon. As machines learn to exchange incompatible data formats, collaboration in the upcoming digital food system will be incentivised, De Gier hopes. In that reborn world, individual companies will experience the luxury of no longer being forced to all move towards one common standard if they want to do business.

Panel discussion & audience questions

Where's the baseline of standardisation between machines? “There are many parameters to define and types of technology to harmonise them so that machines can learn and we can stay decentralised”, Hans de Gier explains in response to Kristian Möller's question. The fundamental requirement is unique universal identification per domain. If all involved in the food chain comply, defining things like location and product is the first firm step towards harmonisation while having a myriad of businesses using different standards.

Can government be kept of the data game? Dick Veerman posed the question to all panelists regarding government in light of the fact that trends seem to indicate that no one is really in favour of government involvement. “Of course we cannot do without government, because we need law somewhere,” commented de Gier. Buisman pointed out that in some countries, such as the United States with USDA, government intervention in the food process is already very strong. Möller points out that the model the organic food industry followed is probably a good guess of how government will come about. The organic food industry’s standards system started on in the private sector, and then the government was called in to help regulate. “Government needs to give us a framework in which the private sector can actually act.” In short: the game should be defined at the grassroots, but governments can - and must - be there for enforcement and to be strict on the boundaries agreed to assure there is no travesty or fraud.

Lastly, de Gier was curious to know whether Buisman thinks the middle men in the food chain will be driven out of business, since digitisation threatens to make their roles superfluous. “In the end you'll see winning companies, Buisman says. They are the ones that consolidate and have modern management styles. "They aim for transparency, and actually use transparency as a commercial instrument.” Buisman believes that it depends on the companies' abilities to adapt. Five to ten years down the road, everything will be transparent and the focus will be on efficiency. Traders who don’t add value to the system and the consumer product will be out.

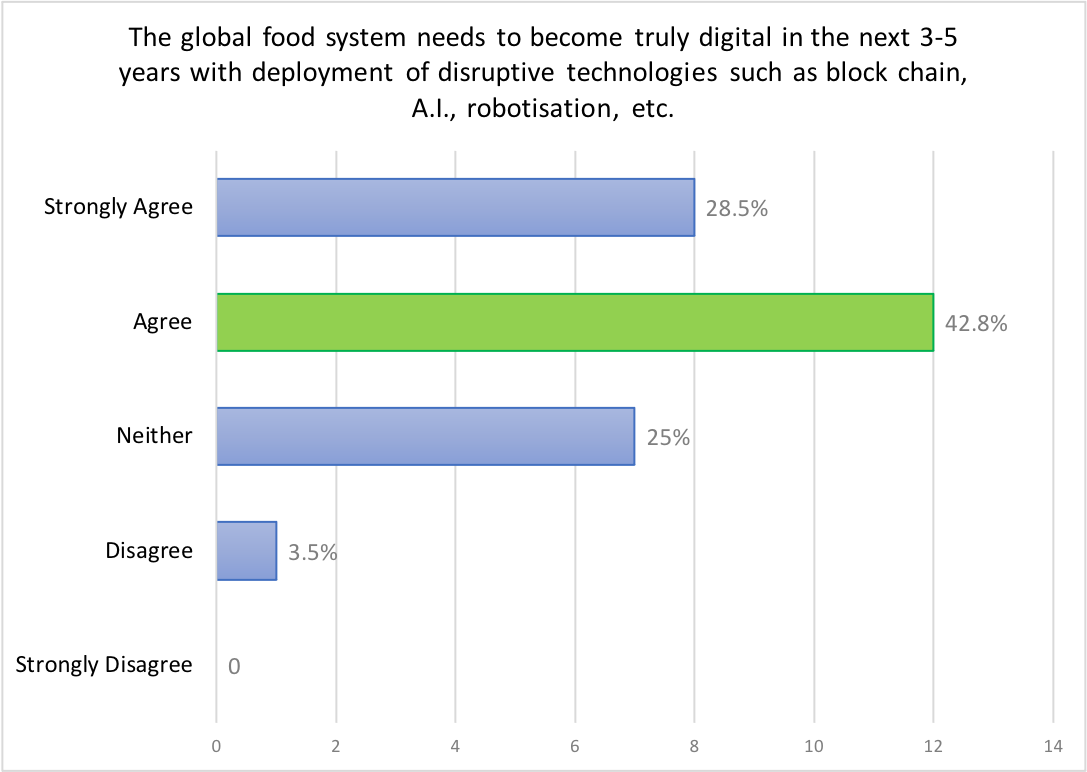

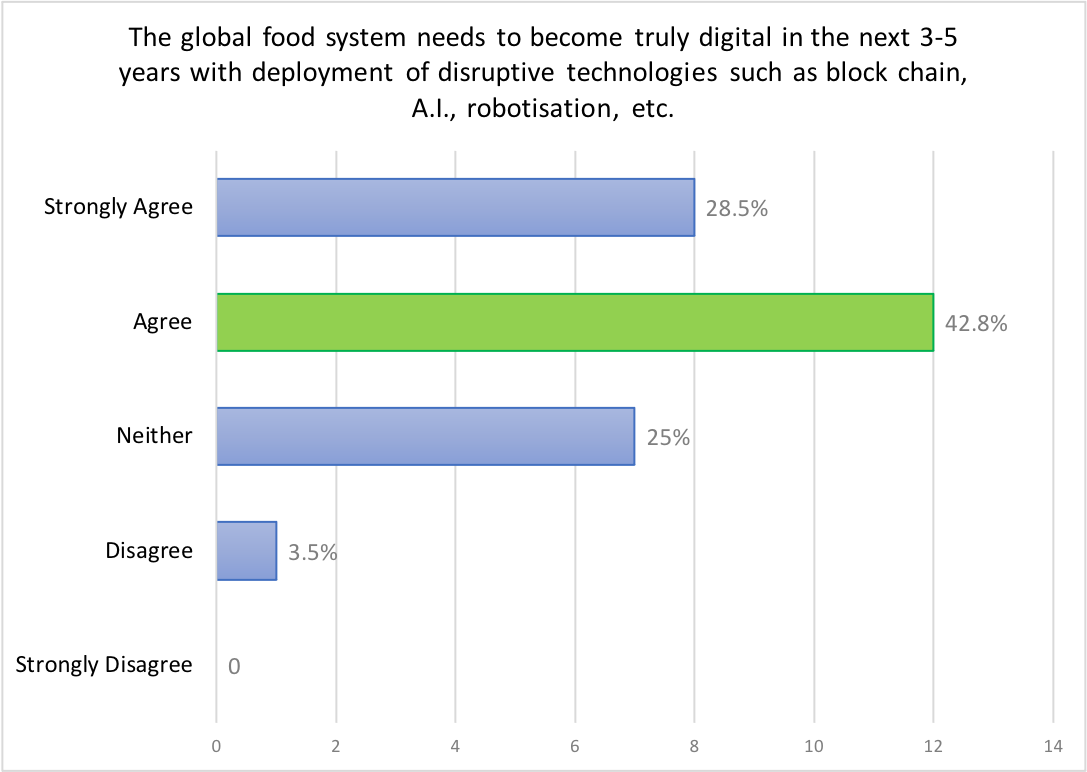

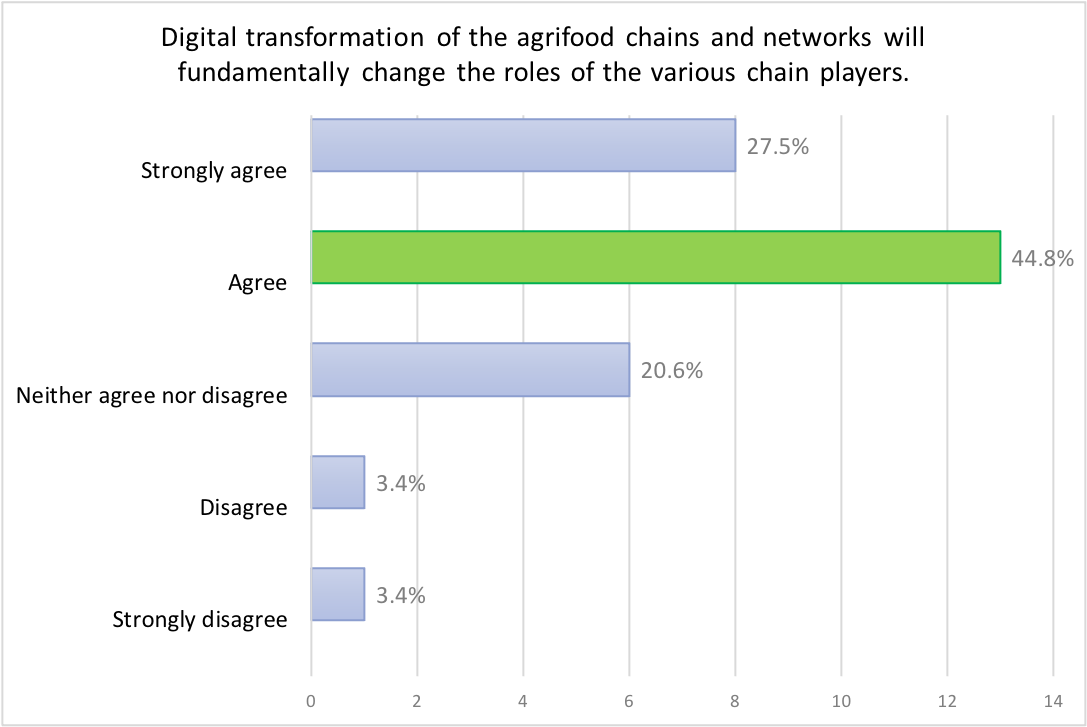

Poll Question #1

AgriFoodNetworks: The global open space between institutions

AgriFoodNetworks is modelled after the Dutch website Foodlog. It is intended to become the same “rare open space” to discuss and engage in conversations “without one person who has the power of authority", explains Foodlog's founder Dick Veerman. On Foodlog everyone is allowed to speak. As long as the participants try to be factual and rational, express and dig for their true feelings and respect one another, there is an open and meaningful discussion.

The value of this kind of open space is crucial in the quickly digitising world of food, Veerman says. Acting as a disruptor, digital technology is so rapidly changing the food system, society needs to decide where it wants it to go. But politics and governments based on typical western democratic political debate won't be fast enough. Digital technology is leap frogging ahead, creating an abyss between practice and law makers. "Before we notice, we'll end up with the equivalents of Facebook and Google in the world of food and find ourselves and governments complaining about it".

Just like Foodlog, AgriFoodNetworks is a place to discuss and assess what is going on and to try to define the kind of future we want, as an open people's parliament influencing media and politics. Veerman, who was originally trained as a political philosopher, considers that a quintessential element in modern society. “Law making government is always behind developments in society", he says. "Digital technology is developing so rapidly that government can hardly catch up anymore". That lays a huge responsibility on the shoulders of the private sector, as it'll have to develop the rules of the new game in the public interest, as well as its own. The private sector cannot do without government, because it needs institutions to ‘keep the game.’ “We create an open space for consumers, businesses, academics, NGO's and regular law makers to tap in and be a kind of global democracy”, Veerman says. At the same time, he intends AgriFoodNetworks to be an open space where business, ideas, and people from all over the globe can meet, connect and create new value while being closely in touch with the wants and needs of real people.

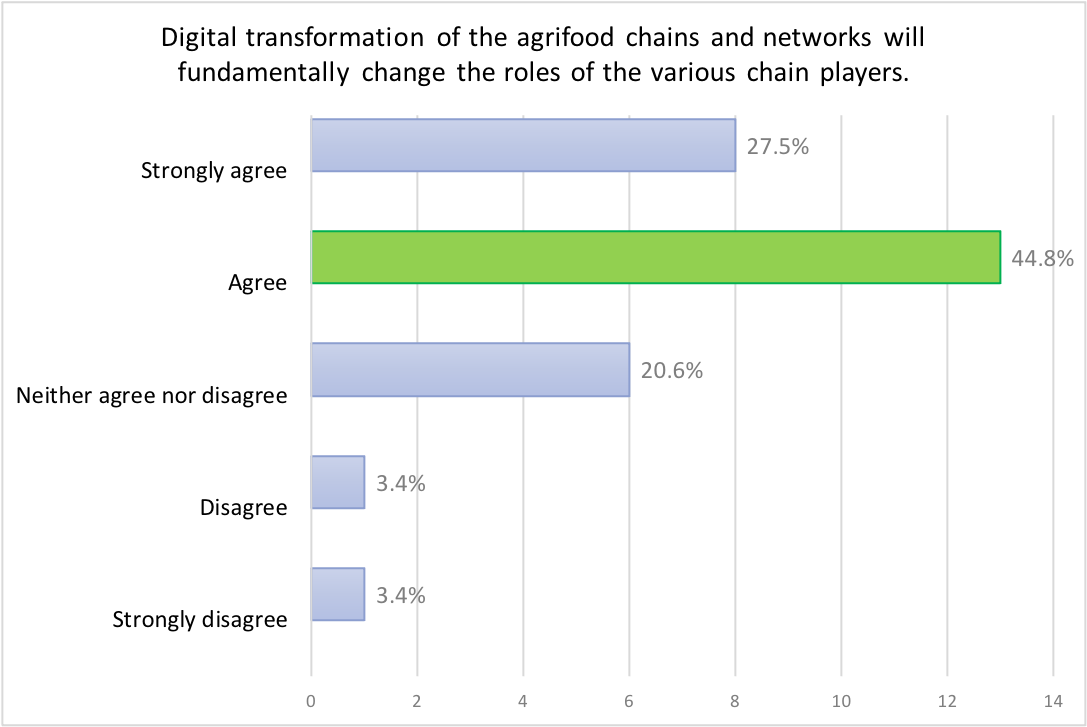

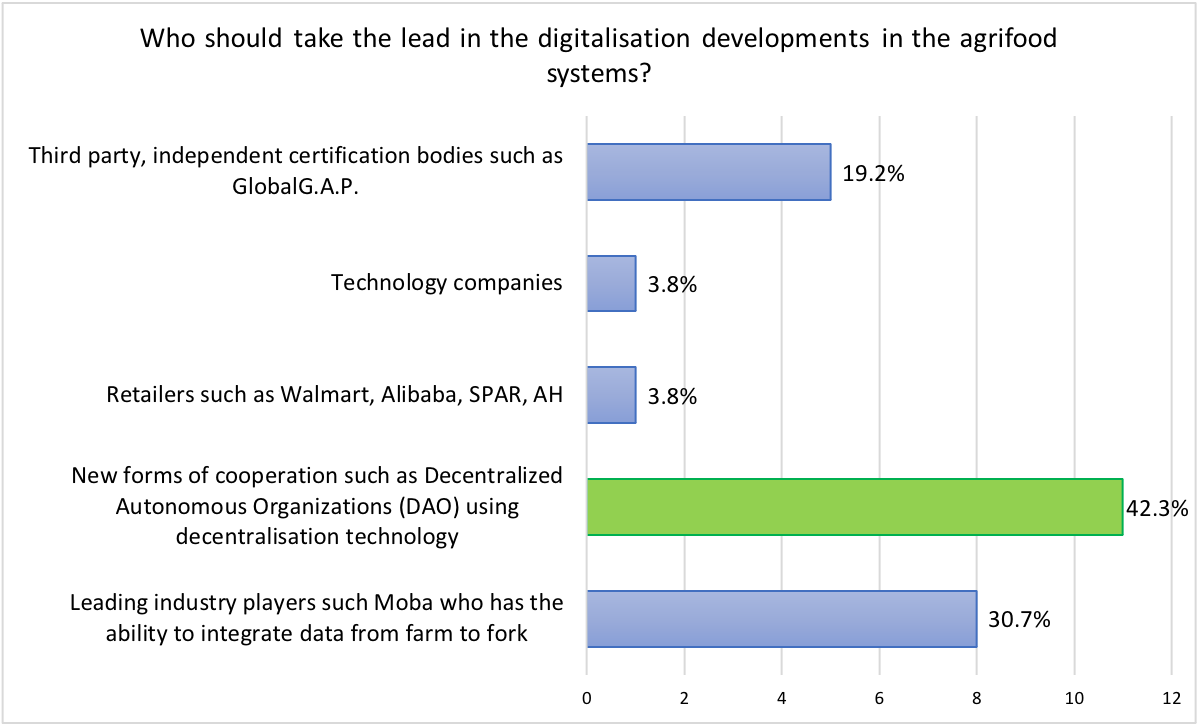

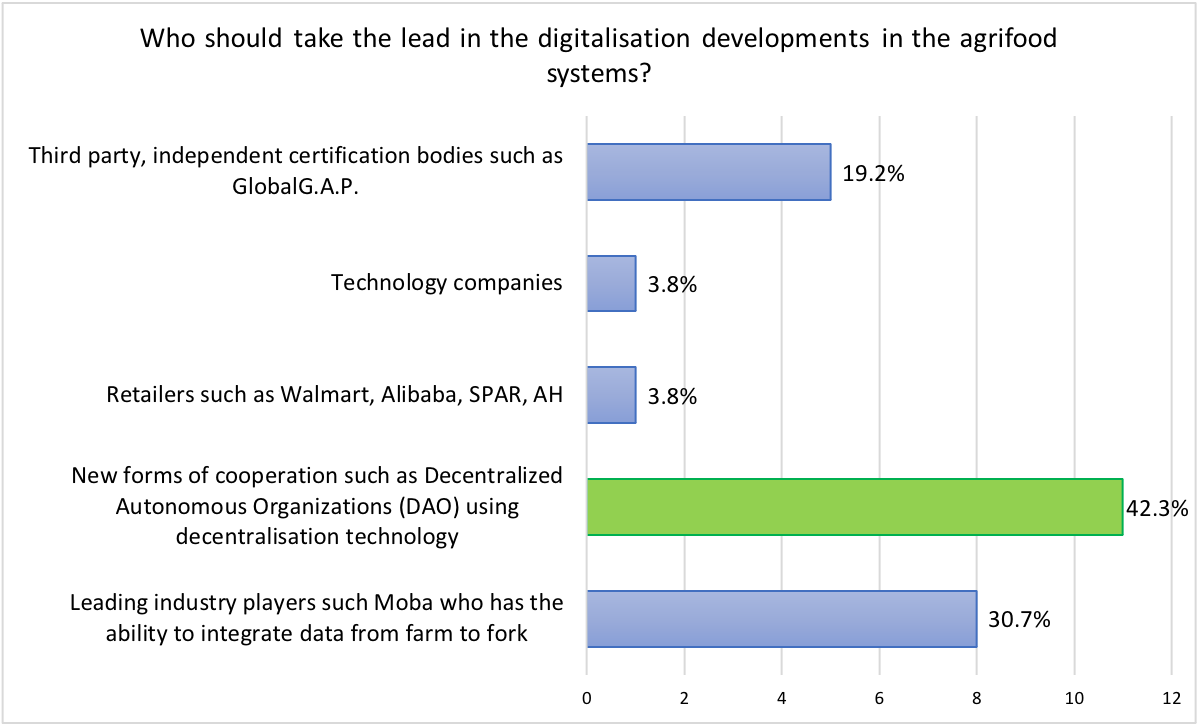

Poll Question #2

Moba: putting 70% of your eggs in one automated basket

Paul Buisman is product management director at Moba, the world's premier egg packing machine maker. Moba’s machines pack, sort, and process over 1 billion eggs a day - that’s over 70% of the automated egg industry market share.

Buisman says companies like his will only survive if they get "on the digital wagon”. He believes that there is no alternative to becoming a part of the world of digital food, and “the winners of tomorrow are the ones that step in today.” However, this doesn’t necessarily entail a complete repositioning of the roles of all actors. Instead of parties adopting new roles, they just have to digitally supplement their existing roles. For example, his machines notice what hens lay best in what climate conditions, as they can automatically monitor the product of one billion of them everyday. That's over 300 billion eggs a year. This kind of information is valuable to all in the food chain as it can be used to improve, for example, animal welfare, the level of production and feed efficiency.

The winners of tomorrow are the ones that step in todayMoba, headquartered in Barneveld, the Netherlands, is responsible for the digitalization of egg production in countries across the world. The company has an annual turnover of €200 million. It produces egg grading, packing, and processing equipment for its customers, which are farms or egg packing stations worldwide. “Ungraded eggs from farms come into our equipment and at the end there are consumer packs with eggs ready for retail,” explains Buisman. Giving a quick overview of the egg industry, Buisman explains eggs are an extremely nutritious commodity. They are a nutrient rich and affordable protein that can be produced at the lowest ecological and economic costs. That's why they are a welcome concentrated natural food source even when income isn’t large.

Worldwide, around 3.5 billion eggs are produced a day. Out of that, 1.3 billion of them are handled automatically. This means the majority of eggs are still the product of backyard farming. 2,2 billion eggs a day are still sold or exchanged "in a little basket or paper bag”, says Buisman. A large part of the back yard volume is expected to be industrialised rather soon and may eventually be processed by Moba machines.

Processing already over 300 billion eggs per year, Moba realised the significance and value of the data the company can easily collect and redistribute. If partners preceding Moba in the chain all add their data, the egg and the processes that created it, will be digitally mirrored. That offers all kinds of information to create new value throughout the whole egg chain.

Moba's approach to data collection is a 3 step procedure.

1. Monitor day to day key performance indicators (KPI’s) to get an overall view of production.

2. Improve performance and efficiency with the ability to compare production results across a network of Moba customers.

3. Chain integration to build in traceability and certification using collected data.

“A packing station gets eggs from many different farms", Buisman says. "We plot quality in a cloud and we have an automatic algorithm that shows you right away how the eggs are doing, without any physical analysis. This gives you an immediate view on farms that aren’t performing.” The data collected after step 1 is split into private and anonymous data once it’s in the cloud. Hence, privacy and data ownership are protected, but anonymous data can still be used to build a network for users for step 2. Buisman points out that while step 1 and 2 are live already, Moba is still working on step 3.

The ones who survive need to be on the digital wagon'The link takes the value'

Moba is currently working on developing “Egg Chain”, a complete track and trace system. With Egg Chain, the simple scanning of a unique product code will tell consumers exactly where their eggs came from or tell Moba customers where their eggs went. The potential for new value creation with regard to improving targeted distribution specificity and efficiency is huge. “We are actually a measurement instrument in the whole production chain", Buisman states stressing the potential for improvement.

Buisman particularly points to the importance of establishing connections between all players in their domains of the food system, even if they seem specific or niche. “How do we interconnect information from different niches? We are in a small niche. Even in our niche there are manufacturers of equipment for building farms who have their own ecosystems and measurement systems." Only the link between the variety of till now unconnected systems takes the value.” Companies like Moba are the logical knot to collect all data before them in the food chain. Their equivalents in the farming world are Lely, the Dutch dairy machine maker at farm level, and Bühler, the Swiss milling machine maker. They could be the next Facebook or Google of food. But none of them intend to do so. Buisman says he isn't even tempted. He wants to serve his customers by helping them to improve their processes and ways of doing business and creating value. In an interview on AgriFoodNetworks, Gijs Scholman from Lely made the exact same statement. Lely doesn't trade data or use it to build power, but instead distributes new knowledge to its web of business partners to better serve their consumers.

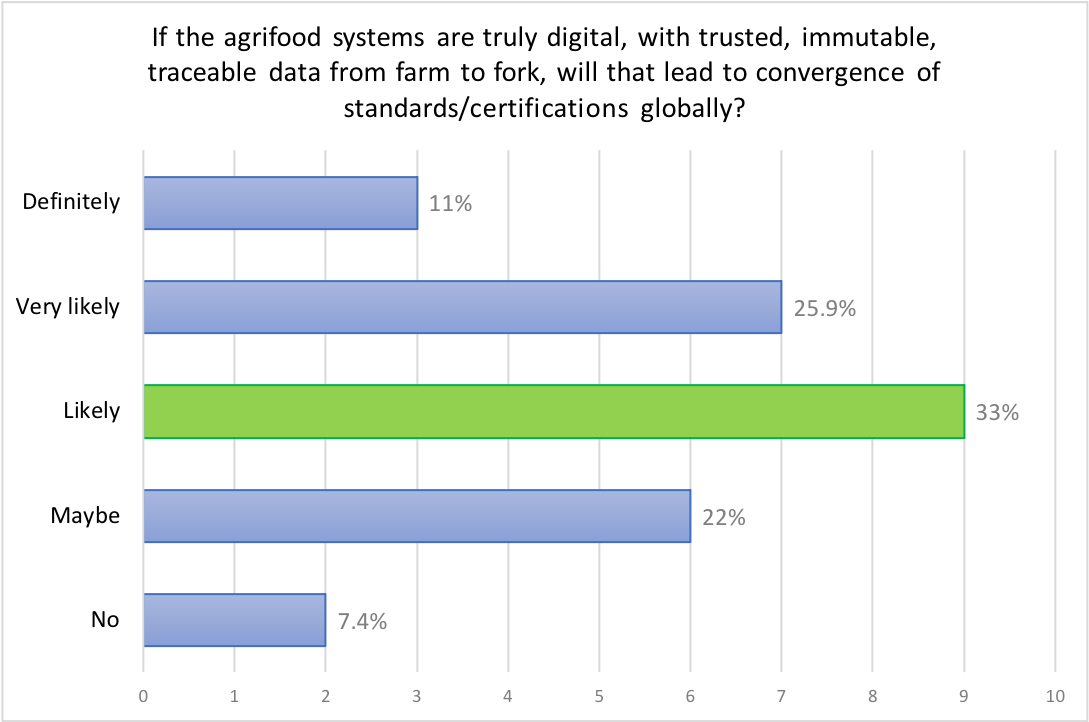

Poll Question #3

GlobalG.A.P.: setting the standard for Good Agricultural Practices

GlobalG.A.P’s Kristian Möller thinks data governance and setting standards in a digitised food world need to be on the priorities' agenda. The initials G.A.P. stand for ‘good agricultural practices’.

Möller's worldwide operating standard setting organisation “started in the area of standard setting when governments weren’t ready. It was actually private sector supply chains that needed standards and efficiency. Industry got together to develop new standards for this sector.” Möller, who is a farmer’s son and entered the industry during the mad cow disease outbreak at the turn of the century, stresses the need to balance traceability and transparency while equally distributing power to all parties involved.

We talk about data harmonisation, but we also need to talk about standards harmonisationGlobalG.A.P. is a standard owner, not a certifier in the field. The organisation cooperates with over 170 certification organisations. The Integrated Farm Assurance Standard (IFA) covers Good Agricultural Practices in agriculture, horticulture, livestock, and aquaculture; it is a modular approach to certification. GlobalG.A.P. is a member driven decision-making structure. With farms and farmers interests as a key priority, the board of the organisation consists of 50% retail players and 50% farmers. Currently, GlobalG.A.P.’s standards touch over 136 countries worldwide, with over 200,000 farmers under certification.

When it comes to industry standards, Möller says, “we talk about data harmonisation, but we also need to talk about standards harmonisation. There’s organic standards, Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance. You have all these different standards organisations.” There are so many standards already that it can be hard to collaborate between them. That’s why in 2014, a group of standard owners signed the Declaration of Abu Dhabi for global food security. “This group of organisations decided we needed to start thinking and rethinking how we share data.”

Three pillars are at the center of the declaration:

1. A common set of practices

2. A farm ID - a system for uniquely identifying every farm that is recognised by all stakeholders

3. Reporting - a mechanism for securing the commitment network sharing of supply chain partners

GlobalG.A.P. introduced farm assurance data exchange, or FAX, a disruptive technology to connect, validate and share data in the supply chain. The organisation first began testing FAX with tech companies to see how it plays out practically. FAX puts an emphasis on bilateral business relationships with service providers and customers. Through research and development, the goal is to come up with the best available technology for the exchange and aggregation of agriculture data.

In the end, we need to find a place where farmers can keep the ownership of their dataWhen circling back to answer poll question #2, Möller says he is opposed to the idea of a new entity to rule the upcoming data game. He thinks that current roles don't necessarily have to change. “If current players are doing it right and we develop an organisational framework and structure by which we can stay in our roles, we can manage together. It’s not one of us", Möller stresses, "that will take the role of being the leader of this new information." At the same time, he agrees with Buisman that new roles need to be added as well, but they won't fundamentally change governance as it is structured today. Möller thinks that all parties should engage in a network of checks and balances of sorts with each other. “Yes, there will be winners and losers and everyone will need to change their role a bit, but it’s only adding to it." Möller fears organisations that will want to be the center or hub for data as they will ultimately accumulate and use the power to control the physical world with data. The goal, however, must be to improve agricultural practices and farmer's incomes. What’s really key, he says, is "making sure that farmers and their data are protected and at the table where the rules are made".

Möller states the role he hopes GlobalG.A.P., allying with farmers, can play in the data sharing process. “When it comes to data and data sharing, I don’t want to be the Silicon Valley based company who has the power to misuse data. GlobalG.A.P. wants to be the custodian where farmers will share their data. Farmers trust us, because they have governance on us. When the data is being shared with others outside of our agreement, they trust us to negotiate on their behalf so that their data aren’t misused. We sit at the table, but we are not the chair and we don’t claim to be the table owner itself. We just want to be sitting on the table with our stakeholders on an equal basis and have an open discussion so that we can build trust among parties.”

The question remains open: what's the nature of a table that nobody owns or chairs? And who keeps the rules of this 'no-body's' super-governance or sanctions those breaching them?

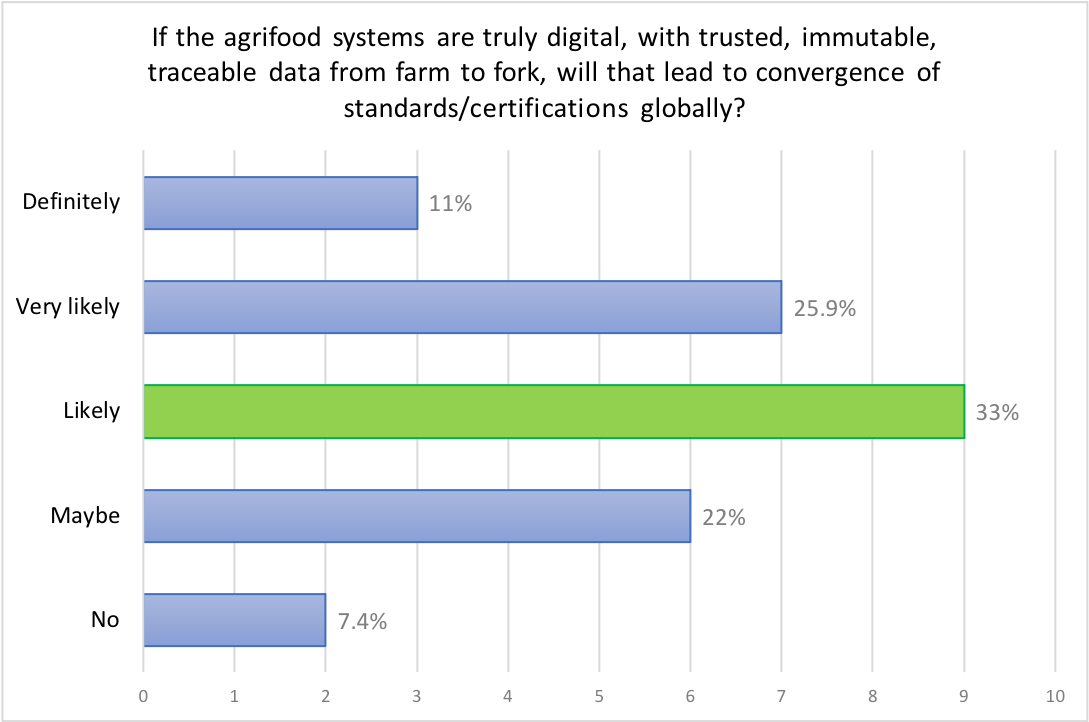

Poll Question #4

DataPorts: making autonomous data transfer “as easy as email”

Hans de Gier, CEO of SyncForce and the speaker of Digital Chat #2: Bye Manpower, Hello Machines and Value. SyncForce's mission is to improve data sharing both within company and between companies and their partners. This allows for a far more efficient flow of information between suppliers, business partners, and customers that isn't bound by standards.

In practice, however, it can result in a complex, expensive, low quality set of tools and procedures as competitors will try to set and impose their standards. Huge interoperability issues lurk just around the cornerIn his short introductory session, De Gier focused on the development of DataPorts, which are systems that will exchange authenticated data with each other directly and autonomously in order to build a trusted network within an end to end value chain.

DataPorts is an initiative of the Consumer Goods Forum (CGF), a network of globally operating companies and organisations that together try to tackle social and environmental sustainability, health & well-being, food safety, and digitisation at a pre-competitive level. The DataPorts concept and the technology to make it come true is inspired by a business need. Commercial organisations want to prove they offer products and services in the interest of society's common goals. In order to stay in business they need the consumer's engagement. That's why being transparent is the name of their game in digitised food markets. "That requires heightened collaboration and 'intelligent value networks'", De Gier says. He believes that “that's almost impossible to have if we don’t have collaboration and digitisation.”

Companies today need systems that aren't just good for business; they also need to be good for wellbeing and the planet. Product success parameters form a 'goodness paradox', says De Gier. Consumers tend to have many distinct or even conflicting ideas of goodness, as do other parties involved.“Everything has to be driven by data in order to standardise efficiency and quality". As de Gier puts it, “the foundation for an intelligent value network is a connected, data driven value network." In practice, however, it can result in a complex, expensive, low quality set of tools and procedures as competitors will try to set and impose their standards. Huge interoperability issues lurk just around the corner. De Gier jokes that there are probably “more standards than companies”.

If everyone can work on the same infrastructure, that will lead to a more harmonised systemThe CGF identified that “we need to have a something that allows machines to exchange data peer-to-peer (P2P), in any standard". It would have to be something as easy as email. That means machines must be able to communicate with other machines without knowing where they are or what kind of application programming interface (API) they have. DataPorts would have to enable autonomous collaborations between machines. “They can reach out to other machines, get answers, and based on that, even do transactions”, De Gier says. Furthermore, this technology should be applicable anywhere in the value network. "It can be built into smart products, software and applications. The only thing these DataPorts need is an address on the other side.”

CGF member Spar imagined replacing category management with intelligent shelves. The shelf asks itself: ‘How much space do I have? What is the weather projection like and how reliable is it? What type of consumer is in the store? What types of products will I need?’ And then it would start sourcing. De Gier stresses that in order to be widely adopted, DataPorts must be low cost, have a low entry barrier, utilise flexible solutioning, grant freedom of choice to users, adopt a global and easy discovery model, and be based on P2P exchange regardless of industry or standard.

Currently, DataPorts are being tested in pilot environments with select companies. Expansion is on the horizon. As machines learn to exchange incompatible data formats, collaboration in the upcoming digital food system will be incentivised, De Gier hopes. In that reborn world, individual companies will experience the luxury of no longer being forced to all move towards one common standard if they want to do business.

Panel discussion & audience questions

Where's the baseline of standardisation between machines? “There are many parameters to define and types of technology to harmonise them so that machines can learn and we can stay decentralised”, Hans de Gier explains in response to Kristian Möller's question. The fundamental requirement is unique universal identification per domain. If all involved in the food chain comply, defining things like location and product is the first firm step towards harmonisation while having a myriad of businesses using different standards.

In the end, winning companies use aim for transparency and use it as a instrumentHow to incentivise or encourage retailers to adopt common standards instead of vying with each other, using individual transparency as a competitive advantage? Moba’s Paul Buisman was curious to learn Kristian Möller's answer, as the latter acknowledged that it’s impossible to avoid duplicating data or standardisation. Möller thinks companies will agree on 80%, or the fundamentals, and will have to negotiate and compromise for the remaining 20%. Furthermore, Möller expects even the big players have already set on generic joint systems because it is difficult and resource consuming to enforce personal systems individually.

Can government be kept of the data game? Dick Veerman posed the question to all panelists regarding government in light of the fact that trends seem to indicate that no one is really in favour of government involvement. “Of course we cannot do without government, because we need law somewhere,” commented de Gier. Buisman pointed out that in some countries, such as the United States with USDA, government intervention in the food process is already very strong. Möller points out that the model the organic food industry followed is probably a good guess of how government will come about. The organic food industry’s standards system started on in the private sector, and then the government was called in to help regulate. “Government needs to give us a framework in which the private sector can actually act.” In short: the game should be defined at the grassroots, but governments can - and must - be there for enforcement and to be strict on the boundaries agreed to assure there is no travesty or fraud.

Government needs to give us a framework in which the private sector can actually actAn audience member takes the question a step further. “When should governments step in?" When do they know enough about these new systems to understand how to protect the weak against those in superposed power positions? Möller thinks that existing government data protection laws, such as the European GDPR agreement can be used as examples and starting points. He also thinks that existing parties that protect the farming industry, such as UN agencies, could participate in education and regulation when the time is right, especially since he thinks there is a role for the UN here in protecting the human right to information.

Lastly, de Gier was curious to know whether Buisman thinks the middle men in the food chain will be driven out of business, since digitisation threatens to make their roles superfluous. “In the end you'll see winning companies, Buisman says. They are the ones that consolidate and have modern management styles. "They aim for transparency, and actually use transparency as a commercial instrument.” Buisman believes that it depends on the companies' abilities to adapt. Five to ten years down the road, everything will be transparent and the focus will be on efficiency. Traders who don’t add value to the system and the consumer product will be out.

Related