Research into alternatives to meat, dairy and eggs is running at full speed. New products are being introduced to the market with great regularity. In addition to the 'traditional' protein transition from animal to plant-based imitation products, cultured meat, fermentation technology and insect proteins offer new and exciting possibilities. Laura te Nijenhuis brings to Foodlog a series of articles on the latest state of the art. Today the first: an overview of some figures, opinions and perspectives on the issue of the climate impact of animal products.

Plant-based food is hip, concludes Cornell University, based on Google statistics. Whereas traditional vegetarians and vegans are mainly concerned with animal suffering in the bio-industry, the focus of the new meat reducers seems to be on health and sustainability. Although there is still no majority among the general public for those who like to eat 100% plant-based foods, the number of flexitarians is growing steadily.

The Dutch government is encouraging plant-based eating to reduce climate change and the carbon emissions associated with the production of animal protein. The December 2020 National Protein Strategy brings the message ‘less animal, more plant’ to the fore. According to a survey (commissioned by ProVeg) published in March 2021, the average Dutch person believes that the government could do more to encourage eating less meat and more plant-based food.

Sensational headlines and documentaries: a one-sided view

Two-thirds of the world's population now regard climate change as a serious issue. Not a week goes by without news about climate issues, and what we ourselves can do to 'do our bit' to limit emissions. Much of this news is specifically about food. Consumers are buffeted with sensational headlines, such as "Going vegan is crucial to help halt the climate crisis" (The Independent) or "Switching to plant-based food can save the world" (RTL). Nice clickbait, but the picture that is painted is rather black and white. Documentaries like Cowspiracy and Forks over Knives grab the viewer with convincingly presented but one-sided arguments about the environmental effects and health of meat versus plant.

Advanced game of Chinese whispers

The lack of nuance starts with the numbers on the food industry's contribution to greenhouse gas emissions. The first clickbait article in the previous paragraph claims that the global food system causes more emissions than anything else. This appears to be taken verbatim from the Chatham House report that the article was based upon. However, the report does not cite a specific number nor does it cite a source. Only further on do the writers mention a figure: 30% of total emissions come from the food industry.

After I did some digging, it turned out that the writers were using the 2019 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report as their source. This IPCC report only says that all "Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU)", i.e. not specifically the food industry, but all cultivation and harvesting for human use, together produces about 23% of total emissions in CO2 equivalents, and much of this is methane, i.e., short-lived carbon. The headlines sound like a convoluted version of the old-fashioned Chinese whispers or Telephone game.

Math is hard

Overall, experts are less united than the news articles would have you believe. Some claim that 26% of total global emissions come from the food industry, and 13% specifically from animal food production. Another cites 11% for all agriculture combined but uses separate figures for industrial processes, which includes food processing and energy consumption. A World Watch Magazine article from 2009 claimed that 51% (!) of total global emissions come specifically from livestock production. As recently as 2013, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) wrote that the livestock industry contributes 14.5% of emissions, based on data from, again, the IPCC.

Are you still following?

Every expert has something to say, and every expert says something different. In our own country as well, juggling with numbers is commonplace. Last year, NGO Milieudefensie calculated that the three largest dairy and meat companies in the Netherlands emit more than all road traffic combined. However, when calculating the emissions, the entire life cycle was considered for animal products but the same was not done for the transport sector.

In 2017, Mark Soetman at Foodlog listed some of these numbers. Soetman said, based on the work of climate expert Stefan Rahmstorf, that the natural closed carbon cycle is often calculated wrongly. Ruminants were emitting methane even before industrial agriculture came into vogue. Cows therefore cannot be the cause of the climate issue. It is not the turnover of carbon already present in the atmosphere that would cause the climate problem but specifically the human addition, the burning of fossil fuels.

In the various studies of emissions from specific product groups in the food industry, the calculation method seems to make quite a difference. The older studies concentrated on emissions per kilogram of product, particularly direct CO2 and methane emissions. Only later the use of agricultural land and water consumption were added, among other things. Although this contributed to a more complete picture, there is still something ‘crooked’ about looking at kilograms of product. A kilo of lettuce does not have the same nutritional value as a kilo of steak.

Looking only at climate impact versus calories doesn't work either. There are as many kilocalories (365) in 100 grams of 45+ cheese as there are in 100 grams of maple syrup. But in terms of environmental impact and nutritional value, these products have little in common.

Nutrient density versus emissions

Meanwhile, researchers are trying to get a handle on the relationship between emissions and nutrient density, where the quantities of specific macro and micronutrients are leading. In the case of animal products, the focus is mainly on easily digestible, high-quality protein. But even that way of looking at it results in guesswork due to the complexity of the issue.

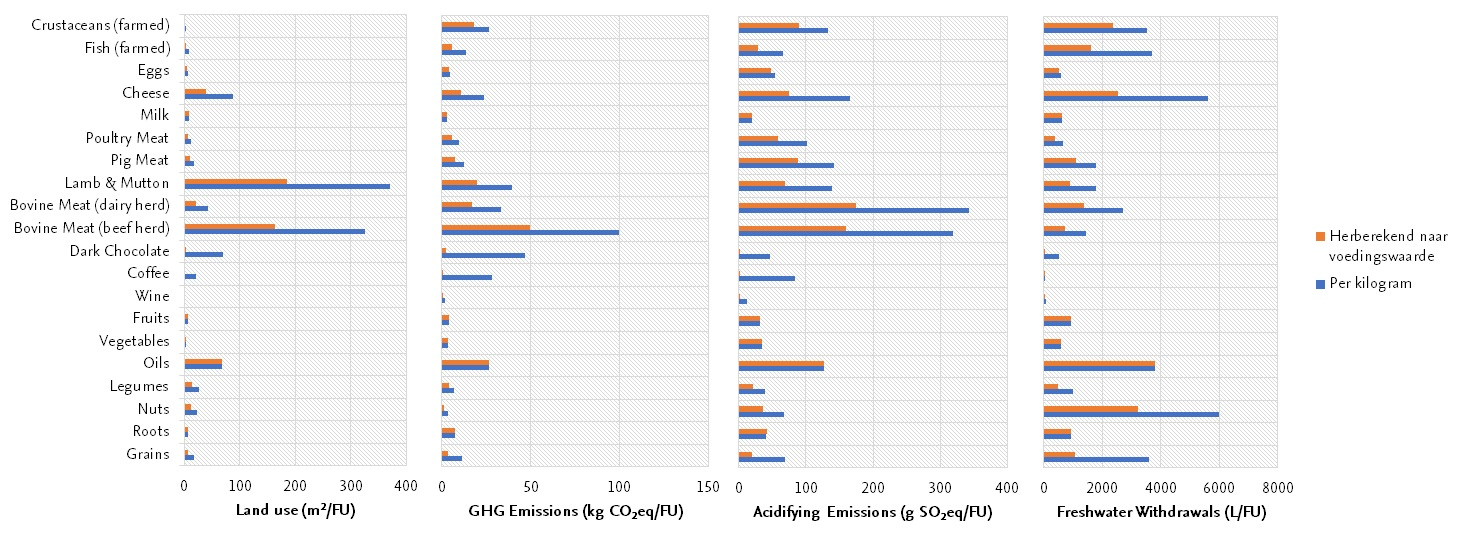

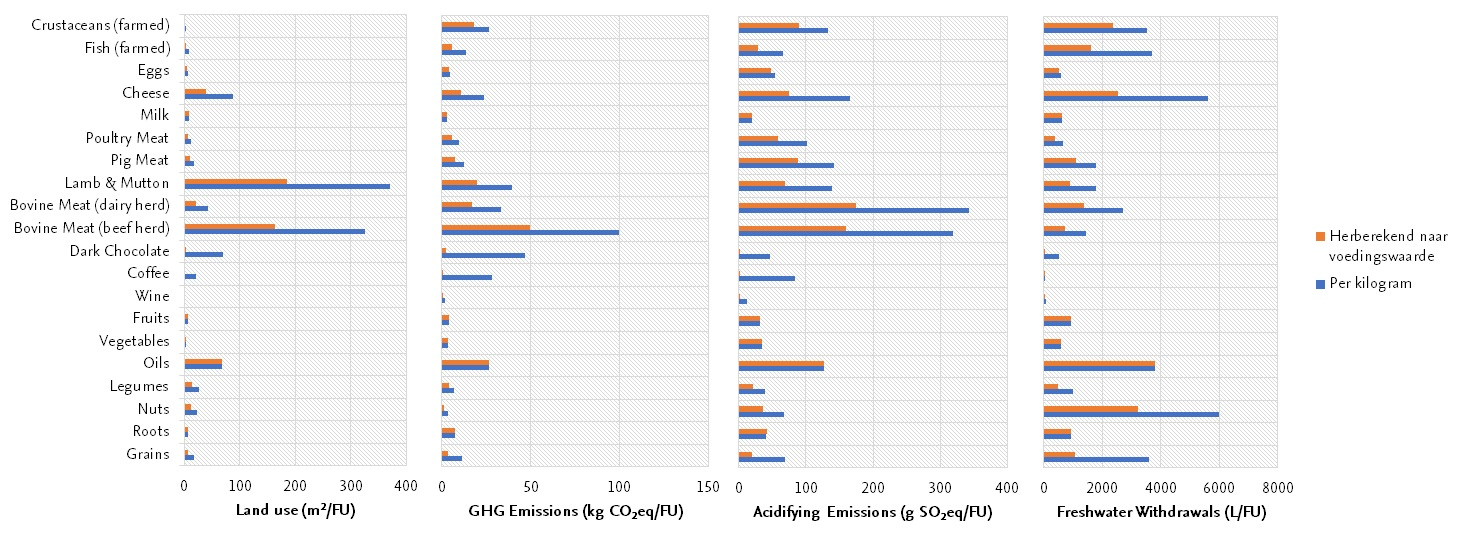

For example, in 2018, Poore and Nemecek calculated the effects of different foods on several environment-related aspects. Land use, water use, emissions in CO2 equivalents and acidification, among others, were considered. The two researchers calculated both effects per kilogram and their contribution to the nutritional value we ingest from products.

Figure 1 was created based on the data from Poore and Nemecek's study. The graph shows how large the differences can be depending on the calculation method and which aspects are included and excluded. For example, there is a clear difference between calculating per kilo (blue) and calculating in nutritional units (red). If only emissions in CO2 equivalents are included, the beef industry clearly performs the 'worst'. In terms of acidification and freshwater use, dairy cows and cheese production score worse. For nuts and shellfish, for example, the differences between the environmental aspects are large. For the overall picture, it also matters which weighting each aspect is given. Which is more important, the fresh water use or the CO2 equivalents? And how do you logically add them up?

In addition, this study does not consider everything that one could theoretically take into account. The researchers did not look at the difference between emissions that fit within the closed loop and the additional emissions that human activity adds. The effects of deforestation and the differences between short-lived and long-lived atmospheric carbon are also not addressed.

Figure 1. Land and water use, GHG and acidifying emissions for different products and product groups. FU stands for functional unit, i.e., kilogram (blue) or nutritional unit (red)

Drewnowski et al. (2015) also looked at the relationship between nutrient density of foods and carbon footprint. This study makes it clear that converting to calories rather than kilograms already makes the differences in emissions between plant and animal-based products much smaller. Including vitamins and minerals in the calculations also showed that nutrient density and emissions often go hand in hand. In the discussion, the researchers explicitly mention that there is a trade-off between sustainability and nutrient density, using the example that sugar, an 'empty' nutrient, has relatively low emissions. In combination with smarter animal husbandry, for example by feeding them inedible plants (leftovers), this trade-off might even result in protein from chicken meat being barely less sustainable than protein from plants. But that also depends on the growing, feeding and calculation methods.

There are countless studies that all say something different and use different methods. Not surprisingly, there is a lot of criticism. To illustrate this point, I list several additional studies and texts at the bottom of this article, for learning and perhaps entertainment.

Plea for nuance

The exact numbers that result from the studies are less important than the conclusions that usually reach the public; the meat and dairy industries are said to contribute significantly to climate change, at least more than most plant-based products.

From 'mainstream' media we therefore mostly hear that meat is bad for the climate, and that a plant-based diet is good. Both the agricultural sector and the scientific community oppose this view. Stopping animal production would have little effect on climate change, especially compared to other solutions.

In this study, the researchers made a model of what would happen if the entire livestock population of the United States were to be shut down. Total GHG emissions of the U.S. would go down 2.6%, according to the calculations. In addition, the animal-free system would be unable to feed the population. If it can be seriously calculated, it is at least an indication that nuance and looking at the whole picture is important.

Another part of the argument that quitting the animal-based food system has little effect is the view that keeping farm animals also has benefits and is even necessary for certain processes. In an entirely plant-based system, for example, the question is where the nutrients for the plants should come from. After all, artificial fertilizer contributes to the climate issue.

An example of someone who is convinced that animals are not the problem is Allen Savory. Savory, educated as a biologist, believes that especially desertification and the loss of greenery had and has a destructive impact. His view is similar to the viewpoint of filmmaker Marijn Poels, who made a documentary on the subject. The two share the conviction that it is precisely a lack of animals, and therefore a lack of nutrients for plants in the form of fertilizer (urine and manure), is the big problem. But you have to choose and put specific animals in specific places. Holistic grazing, Savory calls it. Opinions on Savory's theories are, of course, divided.

However, there may be something in this, according to other researchers. In 2015, the University of Arizona already tested a form of smart grazing to store carbon and regenerate the soil. The result, 30 tons more carbon captured per acre over 10 years than with conventional grazing. Researchers at Michigan State University reached similar conclusions.

More trees, less CO2

In line with Savory's thoughts is the idea that the climate issue is mainly about the balance between the number of trees and the number of people. The current warming would be inversely proportional to the Little Ice Age of the 15th and 16th centuries. With the conquest of the Americas, large numbers of the indigenous peoples disappeared due to the cutting of trees and demolishment of their fields. Where those fields used to be, trees and shrubs were able to regrow uninhibited. As these plants grew, they picked the CO2 out of the air. As a result, it got colder.

If this is the main problem, we should just plant more trees. Sounds simple. There are some hefty hurdles, though. In order to plant enough trees, farmland has to disappear, which means less food. The question is whether this can still be done on degraded land, but Savory's animal tactics might be a solution. Whether optimizing the short cycle by planting trees will help to maintain the existing climate now that the long cycle is already so out of balance due to the burning of fossil fuels, however, remains an unanswered question.

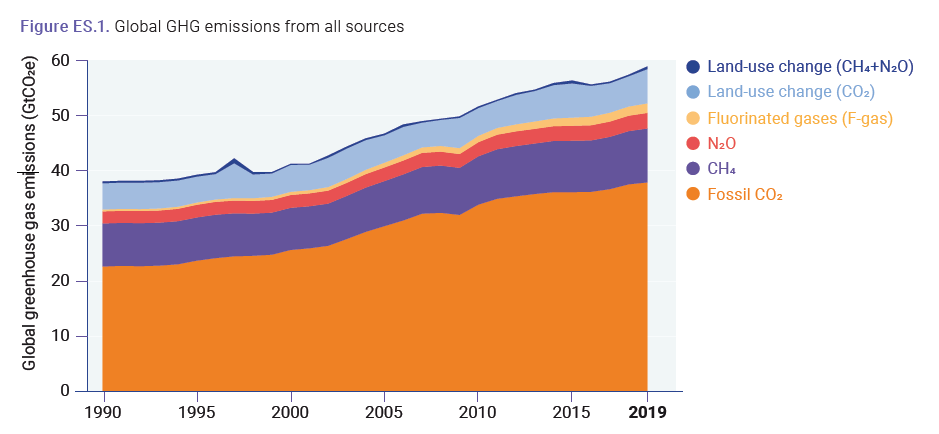

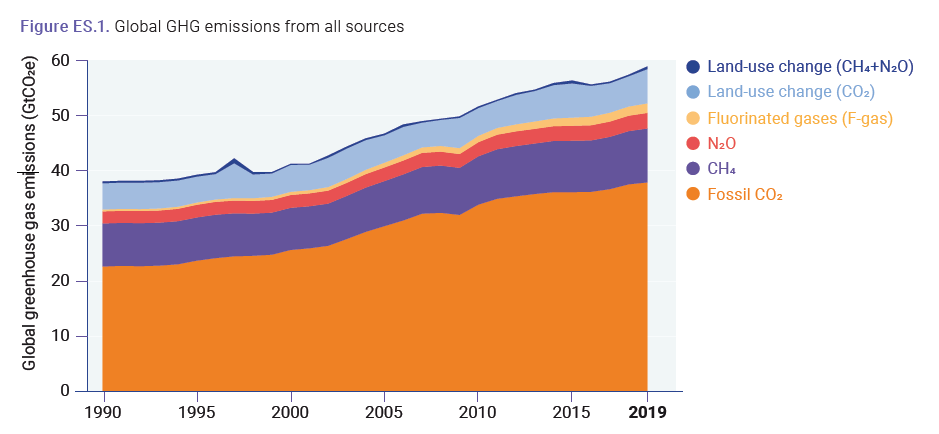

Fossil food

Speaking of fossil fuels, according to many experts, stopping or reducing their use is far more important than what we do with livestock. Releasing carbon that has been stored for millions of years has thrown the balance off. The United Nations Emissions Report (2020) supports this theory. The graph below is from this report and shows that CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion have risen sharply over the past 20 years, while other forms of emissions have remained virtually the same.

Figure 2. Global GHG emissions from all sources, Emissions Gap Report 2020, United Nations Environment Programme

Figure 2. Global GHG emissions from all sources, Emissions Gap Report 2020, United Nations Environment Programme

Ideally, the story of the chicken and the manure should be a circular story. This, however, is not as simple as you might think. Even if the manure is neatly returned to the field, the nutrient cycle is not closed. The chicken grows from the nutrients that come from a field. Then the animal is eaten by us instead of the land being able to claim the carcass back. Some of the nutrients we use for energy and to make new tissue, some disappear into the toilet bowl. In actuality, human manure should also go back to the base to round out the cycle. Jopie Duijnhouwer already calculated on this as a critic of the fashion cycle idea and focused his sums on nitrogen. To make a long story short, the losses in the cycle are great. Duijnhouwer calculated that of all the nitrogen supplied to the farm, less than half ends up in the crop or animal.

To reduce such losses and to conclude this story in a somewhat sinister way, all human remains should have to be used as nutrients for the fields in order to create a truly circular system. You could call it the circle of life. Mankind does not seem to be that enlightened yet, but for the time being just a ‘circular’ field-plant-chicken-manure-land-stream would be a great improvement.

Both Mitloehner and Dutch professors Imke de Boer and Martin Ittersum emphasize that, ecologically speaking, plant remains from a vegan menu are best fed to animals. To make this process as efficient as possible, we should, depending on the region, eat 9 to 23 grams of animal protein per person, per day. Preferably from animals that don't take up much space and like our waste, so chickens and pigs. According to Wageningen University, we are now at 210 grams/day of carcass weight per person, about half that of 'bare' meat. As such, it's not necessarily a question of stopping eating animal products, but of reducing them considerably.

The ideal picture seems to lean towards something like local regenerative circular agriculture with as little fossil fuel and artificial fertilizer use as possible. But how do you implement this in a country with a food agri complex that is so important for the economy and world food supply? “You can't,” states biophysicist and agrobiologist Henk Breman. In an analysis of the agricultural paragraph in the election programme of the political party Groenlinks last year, Breman made it clear that he sees artificial fertilizer and the import of animal feed as a necessary evil. Although he does not believe in nature-inclusive agriculture, because agriculture in any form is hostile to nature, he too supports less overexploitation. To limit damage, negative effects should be avoided as much as possible, but no damage at all is impossible. "Optimal production should replace maximum production," Breman advises.

This 2016 study also implies this and explains the principle from a physics perspective. According to the Maximum Power Principle, when we look at a standard farm as a thermodynamic system, there are two options: maximum yield, or maximum efficiency of using external additives (such as fertilizer) to avoid pollution. Both at the same time cannot be done, and farmers usually and logically still choose the most profitable option. The only way to turn this around, then, is to make it financially interesting for farmers to go for the optimal approach.

Part of a sustainable long-term solution, according to Breman, is to have as few cows as possible. In terms of land use and feed efficiency, cows are the least effective way to feed the world. Moreover, unlike Savory and Poels, Breman thinks it is better to leave the areas where we can let grazers graze naturally to nature in order to sequester CO2. On the other hand, he does see potential in keeping pigs and chickens to process our waste and still produce some animal protein.

Regenerative agriculture

Many of the more nuanced voices against ‘we-must-all-be-vegan-yesterday’ center around the fact that completely abolishing livestock is undesirable, but that how we do it now doesn't work either. There are already farmers who approach their production more like a natural cycle system and manage it well, even financially. The Grazing Farm, inspired by American farmer Joel Salatin who was inspired by Savory-based ideas for his Polyface Farms, and the biodynamic farm GAOS are domestic examples.

In other words, what sensible farming is, sensible people knew all along, and we face the issues humanity faces for a reason. Giller, Sumberg, and two colleagues warn not against regenerative agriculture, but against expectations that are too high.

Idealism versus Feasibility

A movement away from the intensive livestock farming we know in the Western world toward principles such as closed-loop, holistic grazing, nature-inclusive and regenerative agriculture could be part of a balanced solution. However, the meat yield per hectare is considerably lower than in intensive livestock farming, not least because, above all, reduction of the cattle population seems inevitable based on basic agro-biological principles. With this shrinkage, we run into new problems, such as the nutritional aspect and the "but meat/cheese is tasty" mentality that many people have.

In the next article, I will highlight the different technologies that can help us with this.

The Dutch government is encouraging plant-based eating to reduce climate change and the carbon emissions associated with the production of animal protein. The December 2020 National Protein Strategy brings the message ‘less animal, more plant’ to the fore. According to a survey (commissioned by ProVeg) published in March 2021, the average Dutch person believes that the government could do more to encourage eating less meat and more plant-based food.

Documentaries like "Cowspiracy" and "Forks over Knives" grab the viewer with convincingly presented, however one-sided, arguments about the environmental effects and health of meat versus plantThe assumption in all of this is that plant-based would be ‘better’ or at least good. Is that true? To answer these questions, I undertook a research project for Foodlog. What about the emissions from the food sector, are they really that serious? Is this primarily due to livestock farming, or is there more to it than that? Do we really all have to go vegan and do away with livestock?

Sensational headlines and documentaries: a one-sided view

Two-thirds of the world's population now regard climate change as a serious issue. Not a week goes by without news about climate issues, and what we ourselves can do to 'do our bit' to limit emissions. Much of this news is specifically about food. Consumers are buffeted with sensational headlines, such as "Going vegan is crucial to help halt the climate crisis" (The Independent) or "Switching to plant-based food can save the world" (RTL). Nice clickbait, but the picture that is painted is rather black and white. Documentaries like Cowspiracy and Forks over Knives grab the viewer with convincingly presented but one-sided arguments about the environmental effects and health of meat versus plant.

Advanced game of Chinese whispers

The lack of nuance starts with the numbers on the food industry's contribution to greenhouse gas emissions. The first clickbait article in the previous paragraph claims that the global food system causes more emissions than anything else. This appears to be taken verbatim from the Chatham House report that the article was based upon. However, the report does not cite a specific number nor does it cite a source. Only further on do the writers mention a figure: 30% of total emissions come from the food industry.

After I did some digging, it turned out that the writers were using the 2019 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report as their source. This IPCC report only says that all "Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU)", i.e. not specifically the food industry, but all cultivation and harvesting for human use, together produces about 23% of total emissions in CO2 equivalents, and much of this is methane, i.e., short-lived carbon. The headlines sound like a convoluted version of the old-fashioned Chinese whispers or Telephone game.

Math is hard

Overall, experts are less united than the news articles would have you believe. Some claim that 26% of total global emissions come from the food industry, and 13% specifically from animal food production. Another cites 11% for all agriculture combined but uses separate figures for industrial processes, which includes food processing and energy consumption. A World Watch Magazine article from 2009 claimed that 51% (!) of total global emissions come specifically from livestock production. As recently as 2013, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) wrote that the livestock industry contributes 14.5% of emissions, based on data from, again, the IPCC.

Are you still following?

Every expert has something to say, and every expert says something different. In our own country as well, juggling with numbers is commonplace. Last year, NGO Milieudefensie calculated that the three largest dairy and meat companies in the Netherlands emit more than all road traffic combined. However, when calculating the emissions, the entire life cycle was considered for animal products but the same was not done for the transport sector.

In 2017, Mark Soetman at Foodlog listed some of these numbers. Soetman said, based on the work of climate expert Stefan Rahmstorf, that the natural closed carbon cycle is often calculated wrongly. Ruminants were emitting methane even before industrial agriculture came into vogue. Cows therefore cannot be the cause of the climate issue. It is not the turnover of carbon already present in the atmosphere that would cause the climate problem but specifically the human addition, the burning of fossil fuels.

Of course, a kilo of lettuce does not have the same nutritional value as a kilo of steakMethodology makes a difference

In the various studies of emissions from specific product groups in the food industry, the calculation method seems to make quite a difference. The older studies concentrated on emissions per kilogram of product, particularly direct CO2 and methane emissions. Only later the use of agricultural land and water consumption were added, among other things. Although this contributed to a more complete picture, there is still something ‘crooked’ about looking at kilograms of product. A kilo of lettuce does not have the same nutritional value as a kilo of steak.

Looking only at climate impact versus calories doesn't work either. There are as many kilocalories (365) in 100 grams of 45+ cheese as there are in 100 grams of maple syrup. But in terms of environmental impact and nutritional value, these products have little in common.

Nutrient density versus emissions

Meanwhile, researchers are trying to get a handle on the relationship between emissions and nutrient density, where the quantities of specific macro and micronutrients are leading. In the case of animal products, the focus is mainly on easily digestible, high-quality protein. But even that way of looking at it results in guesswork due to the complexity of the issue.

For example, in 2018, Poore and Nemecek calculated the effects of different foods on several environment-related aspects. Land use, water use, emissions in CO2 equivalents and acidification, among others, were considered. The two researchers calculated both effects per kilogram and their contribution to the nutritional value we ingest from products.

Figure 1 was created based on the data from Poore and Nemecek's study. The graph shows how large the differences can be depending on the calculation method and which aspects are included and excluded. For example, there is a clear difference between calculating per kilo (blue) and calculating in nutritional units (red). If only emissions in CO2 equivalents are included, the beef industry clearly performs the 'worst'. In terms of acidification and freshwater use, dairy cows and cheese production score worse. For nuts and shellfish, for example, the differences between the environmental aspects are large. For the overall picture, it also matters which weighting each aspect is given. Which is more important, the fresh water use or the CO2 equivalents? And how do you logically add them up?

In addition, this study does not consider everything that one could theoretically take into account. The researchers did not look at the difference between emissions that fit within the closed loop and the additional emissions that human activity adds. The effects of deforestation and the differences between short-lived and long-lived atmospheric carbon are also not addressed.

Countless studies all say something different and use different methods. Not surprisingly, there is a lot of criticism to be heardHigh nutrient density = high emissions

Drewnowski et al. (2015) also looked at the relationship between nutrient density of foods and carbon footprint. This study makes it clear that converting to calories rather than kilograms already makes the differences in emissions between plant and animal-based products much smaller. Including vitamins and minerals in the calculations also showed that nutrient density and emissions often go hand in hand. In the discussion, the researchers explicitly mention that there is a trade-off between sustainability and nutrient density, using the example that sugar, an 'empty' nutrient, has relatively low emissions. In combination with smarter animal husbandry, for example by feeding them inedible plants (leftovers), this trade-off might even result in protein from chicken meat being barely less sustainable than protein from plants. But that also depends on the growing, feeding and calculation methods.

There are countless studies that all say something different and use different methods. Not surprisingly, there is a lot of criticism. To illustrate this point, I list several additional studies and texts at the bottom of this article, for learning and perhaps entertainment.

Plea for nuance

The exact numbers that result from the studies are less important than the conclusions that usually reach the public; the meat and dairy industries are said to contribute significantly to climate change, at least more than most plant-based products.

From 'mainstream' media we therefore mostly hear that meat is bad for the climate, and that a plant-based diet is good. Both the agricultural sector and the scientific community oppose this view. Stopping animal production would have little effect on climate change, especially compared to other solutions.

In this study, the researchers made a model of what would happen if the entire livestock population of the United States were to be shut down. Total GHG emissions of the U.S. would go down 2.6%, according to the calculations. In addition, the animal-free system would be unable to feed the population. If it can be seriously calculated, it is at least an indication that nuance and looking at the whole picture is important.

Another part of the argument that quitting the animal-based food system has little effect is the view that keeping farm animals also has benefits and is even necessary for certain processes. In an entirely plant-based system, for example, the question is where the nutrients for the plants should come from. After all, artificial fertilizer contributes to the climate issue.

The University of Arizona tested a form of smart grazing to sequester carbon and regenerate soil. The result: 30 tons more carbon captured per acre over 10 years than with conventional grazingMore animals against climate change?

An example of someone who is convinced that animals are not the problem is Allen Savory. Savory, educated as a biologist, believes that especially desertification and the loss of greenery had and has a destructive impact. His view is similar to the viewpoint of filmmaker Marijn Poels, who made a documentary on the subject. The two share the conviction that it is precisely a lack of animals, and therefore a lack of nutrients for plants in the form of fertilizer (urine and manure), is the big problem. But you have to choose and put specific animals in specific places. Holistic grazing, Savory calls it. Opinions on Savory's theories are, of course, divided.

However, there may be something in this, according to other researchers. In 2015, the University of Arizona already tested a form of smart grazing to store carbon and regenerate the soil. The result, 30 tons more carbon captured per acre over 10 years than with conventional grazing. Researchers at Michigan State University reached similar conclusions.

More trees, less CO2

In line with Savory's thoughts is the idea that the climate issue is mainly about the balance between the number of trees and the number of people. The current warming would be inversely proportional to the Little Ice Age of the 15th and 16th centuries. With the conquest of the Americas, large numbers of the indigenous peoples disappeared due to the cutting of trees and demolishment of their fields. Where those fields used to be, trees and shrubs were able to regrow uninhibited. As these plants grew, they picked the CO2 out of the air. As a result, it got colder.

If this is the main problem, we should just plant more trees. Sounds simple. There are some hefty hurdles, though. In order to plant enough trees, farmland has to disappear, which means less food. The question is whether this can still be done on degraded land, but Savory's animal tactics might be a solution. Whether optimizing the short cycle by planting trees will help to maintain the existing climate now that the long cycle is already so out of balance due to the burning of fossil fuels, however, remains an unanswered question.

Fossil food

Speaking of fossil fuels, according to many experts, stopping or reducing their use is far more important than what we do with livestock. Releasing carbon that has been stored for millions of years has thrown the balance off. The United Nations Emissions Report (2020) supports this theory. The graph below is from this report and shows that CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion have risen sharply over the past 20 years, while other forms of emissions have remained virtually the same.

Figure 2. Global GHG emissions from all sources, Emissions Gap Report 2020, United Nations Environment Programme

Figure 2. Global GHG emissions from all sources, Emissions Gap Report 2020, United Nations Environment ProgrammeTo cut a long story short, the losses in the cycle are considerable. Duijnhouwer has calculated that of all the nitrogen supplied to the farm, less than half ends up in the crop or in the animalSpecifically, within the livestock industry, the use of fossil fuels is related, among other things, to feeding imported grains instead of plant residues and natural grazing. Foodlog founder Dick Veerman explained this clearly in 2017: a kilogram of feed yields a maximum of 450 grams of meat (provided it is a fast-growing industrial broiler chicken). That chicken defecates part of it again. In theory, this should be returned to the fields where the feed was grown. Those fields are quite far away (North and South America) and return transport is too expensive. Instead of return transport, we burn the chicken manure in the Netherlands. In doing so, we remove essential nutrients from the cycle and make artificial fertilizer over and over again to have new feed made in a country on the other side of the world. Fertilizer is cheaper to make and transport. However, the problem arises that making and transporting fertilizer requires fossil fuels, and using them messes up the organic matter cycle.

Ideally, the story of the chicken and the manure should be a circular story. This, however, is not as simple as you might think. Even if the manure is neatly returned to the field, the nutrient cycle is not closed. The chicken grows from the nutrients that come from a field. Then the animal is eaten by us instead of the land being able to claim the carcass back. Some of the nutrients we use for energy and to make new tissue, some disappear into the toilet bowl. In actuality, human manure should also go back to the base to round out the cycle. Jopie Duijnhouwer already calculated on this as a critic of the fashion cycle idea and focused his sums on nitrogen. To make a long story short, the losses in the cycle are great. Duijnhouwer calculated that of all the nitrogen supplied to the farm, less than half ends up in the crop or animal.

To reduce such losses and to conclude this story in a somewhat sinister way, all human remains should have to be used as nutrients for the fields in order to create a truly circular system. You could call it the circle of life. Mankind does not seem to be that enlightened yet, but for the time being just a ‘circular’ field-plant-chicken-manure-land-stream would be a great improvement.

The only correct solution, according to Mitloehner, is to stop burning fossil fuels altogetheAnimals are not the culpritsDr. Frank Mitloehner, a professor at the University of Davis California, has a more moderate view of the whole matter. Mitloehner, with the appropriate Twitter handle GHGGuru, is an expert on the relationship between livestock farming and air quality and has been trying to make it clear for years that eliminating meat has less of an impact than the public thinks. In a February 2021 interview, he and Mark Soetman also revisit that 14.5% of emissions come from the FAO's livestock industry. Soetman mentions that in the discussion on this subject it is often forgotten that a carbon cycle is simply part of a world with carbon-based life. Mitloehner agrees. The problem is not the keeping and eating of animals as such, but all those fossil fuels we use to make things more efficient and faster. And more luxurious. At a symposium in 2019, according to Vilt.be, Mitloehner mentioned that eating vegan for a year has about half the effect of cancelling one transatlantic flight. This ’shame of flying’, that many Europeans feel, comes not completely out of the blue (although living car-free is still a lot more effective). The only correct solution, according to Mitloehner, is to stop burning fossil fuels altogether.

Both Mitloehner and Dutch professors Imke de Boer and Martin Ittersum emphasize that, ecologically speaking, plant remains from a vegan menu are best fed to animals. To make this process as efficient as possible, we should, depending on the region, eat 9 to 23 grams of animal protein per person, per day. Preferably from animals that don't take up much space and like our waste, so chickens and pigs. According to Wageningen University, we are now at 210 grams/day of carcass weight per person, about half that of 'bare' meat. As such, it's not necessarily a question of stopping eating animal products, but of reducing them considerably.

Optimal production must replace maximum productionNature-inclusive circular agriculture does not exist?

The ideal picture seems to lean towards something like local regenerative circular agriculture with as little fossil fuel and artificial fertilizer use as possible. But how do you implement this in a country with a food agri complex that is so important for the economy and world food supply? “You can't,” states biophysicist and agrobiologist Henk Breman. In an analysis of the agricultural paragraph in the election programme of the political party Groenlinks last year, Breman made it clear that he sees artificial fertilizer and the import of animal feed as a necessary evil. Although he does not believe in nature-inclusive agriculture, because agriculture in any form is hostile to nature, he too supports less overexploitation. To limit damage, negative effects should be avoided as much as possible, but no damage at all is impossible. "Optimal production should replace maximum production," Breman advises.

Unlike Savory and Poels, Breman thinks that the places where we can let grazers graze naturally are better left to nature in order to sequester CO2. On the other hand, he too sees something to be gained from keeping pigs and chickensChickens

This 2016 study also implies this and explains the principle from a physics perspective. According to the Maximum Power Principle, when we look at a standard farm as a thermodynamic system, there are two options: maximum yield, or maximum efficiency of using external additives (such as fertilizer) to avoid pollution. Both at the same time cannot be done, and farmers usually and logically still choose the most profitable option. The only way to turn this around, then, is to make it financially interesting for farmers to go for the optimal approach.

Part of a sustainable long-term solution, according to Breman, is to have as few cows as possible. In terms of land use and feed efficiency, cows are the least effective way to feed the world. Moreover, unlike Savory and Poels, Breman thinks it is better to leave the areas where we can let grazers graze naturally to nature in order to sequester CO2. On the other hand, he does see potential in keeping pigs and chickens to process our waste and still produce some animal protein.

Regenerative agriculture

Many of the more nuanced voices against ‘we-must-all-be-vegan-yesterday’ center around the fact that completely abolishing livestock is undesirable, but that how we do it now doesn't work either. There are already farmers who approach their production more like a natural cycle system and manage it well, even financially. The Grazing Farm, inspired by American farmer Joel Salatin who was inspired by Savory-based ideas for his Polyface Farms, and the biodynamic farm GAOS are domestic examples.

Giller, Sumberg and two colleagues warn not against regenerative agriculture, but against overly high expectationsThe ‘Kiss the Ground’ documentary - with Woody Harrelson and other well-known Hollywood stars - seems to be maturing minds for a focus on regenerative agriculture that treats the soil better and traps carbon in it. The IPCC happily joined in, adding to its claim that regenerative agriculture can help save the planet. "The potential for carbon sequestration in soils via agriculture can play an important role in mitigating climate change," and smart grazing with animals may be part of that. However, as stated by recently lauded academic agronomists Ken Giller and James Sumberg, don't act like regenerative agriculture is something new.

In other words, what sensible farming is, sensible people knew all along, and we face the issues humanity faces for a reason. Giller, Sumberg, and two colleagues warn not against regenerative agriculture, but against expectations that are too high.

Idealism versus Feasibility

A movement away from the intensive livestock farming we know in the Western world toward principles such as closed-loop, holistic grazing, nature-inclusive and regenerative agriculture could be part of a balanced solution. However, the meat yield per hectare is considerably lower than in intensive livestock farming, not least because, above all, reduction of the cattle population seems inevitable based on basic agro-biological principles. With this shrinkage, we run into new problems, such as the nutritional aspect and the "but meat/cheese is tasty" mentality that many people have.

In the next article, I will highlight the different technologies that can help us with this.

Related

Business wise I love all communication about protein transition, about more plant-based and vegen/vega. But as scientist I strongly doubt by bullying the meat-industry when it comes to global heating. I also have the feeling that repeating over and over the same numbers regarding GHG and land-usage will not stimulate large groups of consumers to make a shift. What is needed: great taste, great taste, grease of plant-based. And fair prices per kg. Scalability thus and not more basic or fundamental research.

Thank you for this article, with much needed rationality.