With the climate changing drastically and agriculture contributing to a large part of the emissions responsible for these developments, rethinking the way we practice and interact with agriculture is a necessity. Therefore humanity needs to focus on the role of animal-and plant-based proteins in agriculture. Not only in terms of their environmental impacts, but also with regard to the associated socio-economic effects.

A wide range of Life Cycle Assessments show that animal-based proteins contribute to high levels of Global Warming Potential, Acidification and Eutrophication Potential, whereas plant-based proteins only scored higher in terms of energy use, due to some LCAs focusing solely on greenhouse cultivation. These trends already indicate the positive environmental effects of a protein transition. Still, a successful transition does not only imply improvements in producing animal-based proteins, but also requires a rethinking of crop cultivation and the types of crops being planted.

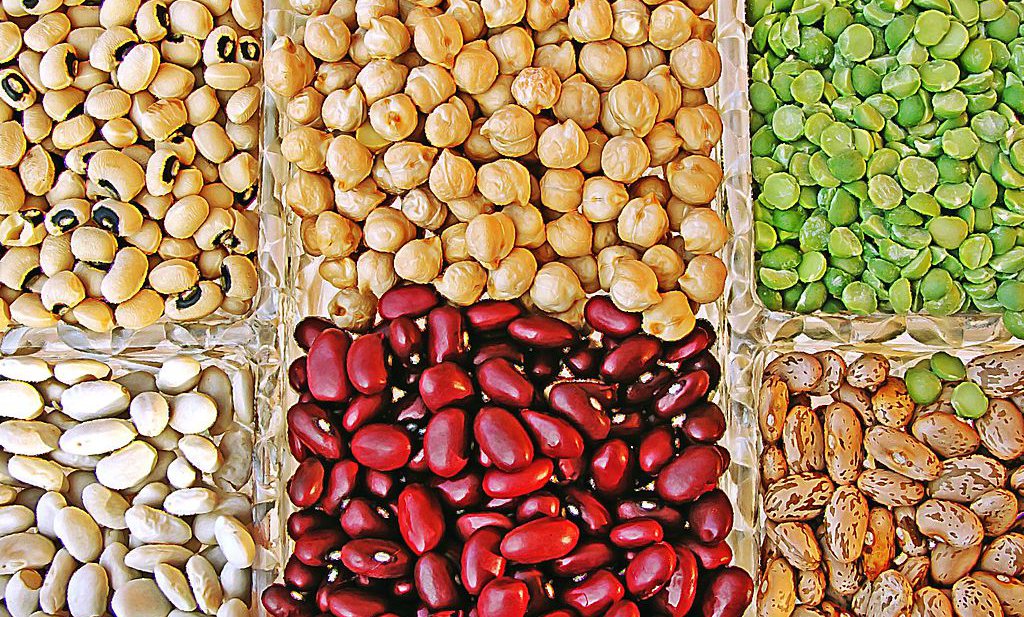

The general transition towards more specialized and intensive production systems resulted in technological lock-ins, where agricultural standards and production norms are now difficult to change or adapt. Currently, higher amounts of diversity in crops are not sufficiently rewarded by the EU, leading to further discouragement of cultivating legumes. Cultural transformations have further lowered the regard for legume and pulse cultivation, as for example lentils are now often considered as an old-fashioned and uninteresting food, and together with a long preparation time, are not considered as practical for the more fast-paced types of cooking done today. To improve the legumes’ image, as well as its profitability and yield reliability, new policies are needed, together with improved knowledge on how to manage crop rotations, as well as improvements on a genetic level.

An increase in legume cultivation would bring with it a reduced need for fertilizer, as the plants possess the ability to biologically fixate nitrogen, i.e., preventing nutrient leaching on a larger scale. Additionally, if used as part of a crop rotation, legumes positively impact the yields of the following crops, and simultaneously improve soil quality. Furthermore, their protein content is relatively high, as are its other nutrients, therefore providing a solid alternative or complement to meat products.

The protein transition does not only offer the opportunity to rediscover the benefits of legume cultivation, but also the many plant species varieties that exist. Given the already tangible adverse effects of climate change on agriculture in terms of lower crop yields due to droughts and degraded soils, ensuring yield stability and food security will remain one of the main priorities for the upcoming decades. However, it is not only aridity that has impacted soils, but also the use of monocultures that reduce nutrient availability, and in more general terms, biodiversity. Similar to legume cultivation, plant genetic diversity has been decreasing over the last few decades, with less than 10% of fruit and vegetable genetic diversity remaining. Despite the arguably high importance for food security of the few high-yielding staple crops available in the supermarket, rare and local species are an important factor for the sustainable cultivation of plant proteins.

Additionally, returning to a cultivation of more legumes and other local varieties has the potential to reduce the dependency of farmers on large multinationals not only for fertilizer inputs, but also for seeds, which in many cases must be purchased every year, instead of saved by the farmers themselves. The opportunity of refocusing of the current large-scale plant cultivation system in terms of an emphasis on legumes and local varieties has many benefits, but also comes with its constraints. As mentioned above, legumes and other local and rare varieties are less stable in their yields as high-yielding staple crops. Therefore, completely abandoning the cultivation of the latter is not feasible, especially given food security concerns. However, dedicating a portion of the land to these other crops, and rethinking their production methods could prove beneficial on the farm level. Another constraint linked to the instability of yields is their effect on farmer income, as well as the often-higher costs of implementing the previously mentioned changes. Therefore, a redistribution of agricultural subsidies not solely based on farm size but rather production method and type of farm is necessary.

All in all, a protein transition should not only advocate for a revised role of the animal and its associated production impacts, but also consider the detrimental impacts of the current plant-protein production systems, such as extensive monocultures that rely on heavy fertilizer inputs and multinational corporations for seeds. Instead, a focus on rediscovering the various agricultural and nutritional benefits of legumes and local and rare varieties (including their crop wild relatives) must be included in the discussion - and ultimately legislation - around the protein transition.

The protein transition does not only offer the opportunity to rediscover the benefits of legume cultivation, but also the many plant species varieties that existA reduction in animal-based proteins would prove to be even more beneficial if it was accompanied by a move away from crop monocultures, such as an increase in legume cultivation and consumption, as well as a focus on breeding more rare and local species. The recent decades have witnessed a decline in legume consumption, mostly due to yield fluctuations and low profits leading farmers to turn away from their cultivation. The reason for this undervaluation of grain legumes in the current agricultural system is a mix of policy incentives, as well as technological lock-ins and cultural shifts. EU CAP subsidy changes in the 1960s to 1980s led to the neglect of minor crops and shifted towards a focus on soy imports for protein rich animal feed.

The general transition towards more specialized and intensive production systems resulted in technological lock-ins, where agricultural standards and production norms are now difficult to change or adapt. Currently, higher amounts of diversity in crops are not sufficiently rewarded by the EU, leading to further discouragement of cultivating legumes. Cultural transformations have further lowered the regard for legume and pulse cultivation, as for example lentils are now often considered as an old-fashioned and uninteresting food, and together with a long preparation time, are not considered as practical for the more fast-paced types of cooking done today. To improve the legumes’ image, as well as its profitability and yield reliability, new policies are needed, together with improved knowledge on how to manage crop rotations, as well as improvements on a genetic level.

An increase in legume cultivation would bring with it a reduced need for fertilizer, as the plants possess the ability to biologically fixate nitrogen, i.e., preventing nutrient leaching on a larger scale. Additionally, if used as part of a crop rotation, legumes positively impact the yields of the following crops, and simultaneously improve soil quality. Furthermore, their protein content is relatively high, as are its other nutrients, therefore providing a solid alternative or complement to meat products.

The protein transition does not only offer the opportunity to rediscover the benefits of legume cultivation, but also the many plant species varieties that exist. Given the already tangible adverse effects of climate change on agriculture in terms of lower crop yields due to droughts and degraded soils, ensuring yield stability and food security will remain one of the main priorities for the upcoming decades. However, it is not only aridity that has impacted soils, but also the use of monocultures that reduce nutrient availability, and in more general terms, biodiversity. Similar to legume cultivation, plant genetic diversity has been decreasing over the last few decades, with less than 10% of fruit and vegetable genetic diversity remaining. Despite the arguably high importance for food security of the few high-yielding staple crops available in the supermarket, rare and local species are an important factor for the sustainable cultivation of plant proteins.

Planting local and rare varieties does not only improve micronutrient availability in the soil and the plant but crossbreeding with wild plant genetic relatives can result in a higher drought and heat stress resistance of the cropPlanting local and rare varieties does not only improve micronutrient availability in the soil and the plant but crossbreeding with wild plant genetic relatives can result in a higher drought and heat stress resistance of the crop. Together with measures like intercropping or strip cropping, where crops are planted next to each other in small to medium-size strips, an increased genetic diversity also helps to prevent pests and diseases that could decimate the yield. In more general terms, shifting towards more sustainable production methods such as agroecology or regenerative agriculture must be considered, however, elaborating on the implications of doing so merits its own blog article.

Additionally, returning to a cultivation of more legumes and other local varieties has the potential to reduce the dependency of farmers on large multinationals not only for fertilizer inputs, but also for seeds, which in many cases must be purchased every year, instead of saved by the farmers themselves. The opportunity of refocusing of the current large-scale plant cultivation system in terms of an emphasis on legumes and local varieties has many benefits, but also comes with its constraints. As mentioned above, legumes and other local and rare varieties are less stable in their yields as high-yielding staple crops. Therefore, completely abandoning the cultivation of the latter is not feasible, especially given food security concerns. However, dedicating a portion of the land to these other crops, and rethinking their production methods could prove beneficial on the farm level. Another constraint linked to the instability of yields is their effect on farmer income, as well as the often-higher costs of implementing the previously mentioned changes. Therefore, a redistribution of agricultural subsidies not solely based on farm size but rather production method and type of farm is necessary.

All in all, a protein transition should not only advocate for a revised role of the animal and its associated production impacts, but also consider the detrimental impacts of the current plant-protein production systems, such as extensive monocultures that rely on heavy fertilizer inputs and multinational corporations for seeds. Instead, a focus on rediscovering the various agricultural and nutritional benefits of legumes and local and rare varieties (including their crop wild relatives) must be included in the discussion - and ultimately legislation - around the protein transition.

This article is the first in a series written by Clémentine Dècle-Classen, Ana-Maria Gătejel, Vivien Vent, Simon Wessels regarding the protein transition. They have explored the protein transition from each of their unique points of view based on their group study. They are Master students at Leiden University.

Related