Watching Hannah Ritchie make a meal looks like an environmental travesty. It looks like the opposite of what seems sustainable. But it's not. That's why we need to change our images of what really are 'environmentally-friendly’ behaviours, she says.

My charts might be plastered across posters about the environment, but I’ll never be a poster girl for environmental action.

Watching me make a meal looks like an environmental travesty. I almost exclusively use the microwave. I don’t take time to savour the process: a meal that takes longer than ten minutes is one that’s not worth having. It nearly always comes from a packet. My avocados are shipped over from Mexico, and bananas transported from Angola. It’s rare that my food is produced locally. Or if it is, I don’t check the label enough to notice.

This is the opposite of what seems sustainable. The image we have in our head of the ‘environmentally-friendly meal’ is one that’s sourced from the local market; produced on an organic farm without nasty chemicals; and brought home in a paper bag, not a plastic wrapper. Forget the processed junk: it’s meat and vegetables, as fresh as they come. We set aside time to cook them properly, in the oven.

I know that my way of eating is low-carbon. I’ve spent years poring over the data. Microwaves are the most efficient way to cook. Local food is often no better than food shipped from continents away. Organic food often has a higher carbon footprint. And packaging is a tiny fraction of a food’s environmental footprint, and often lengthens its shelf-life.

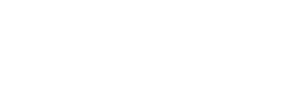

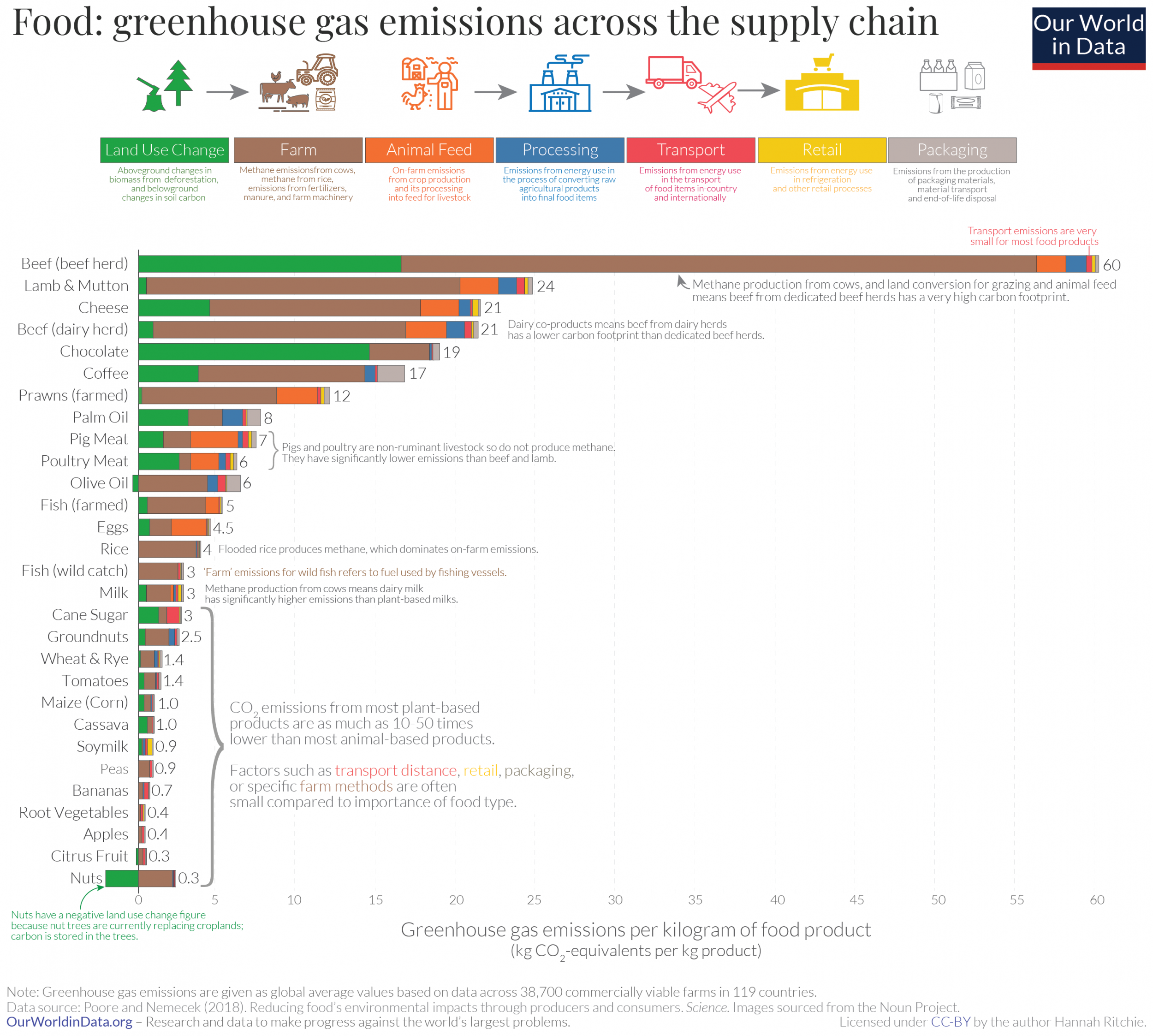

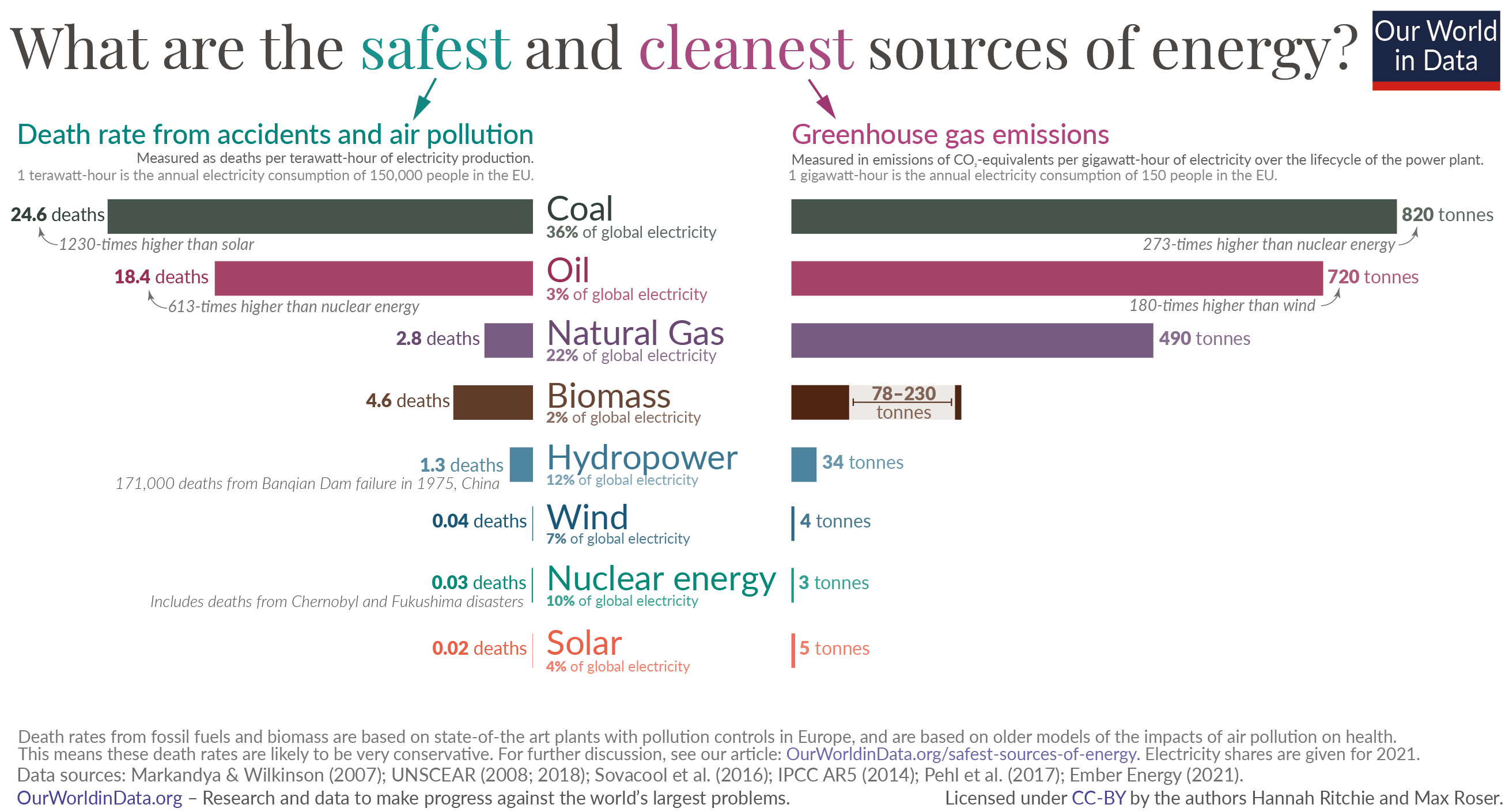

Bron: Our world in data

Bron: Our world in data

Yet it still feels wrong. I know I’m doing the right thing for the environment, but there’s still a part of me that feels like a traitor. I can see the confusion on peoples’ faces when they hear about some of my decisions. I feel embarrassed that people might think that I’m being a ‘bad’ environmentalist.

This problem stems from the fact that what is ‘good’ for the environment often doesn’t line up with our intuitions. Ask people about what behaviours are most effective in reducing their carbon footprint, and they talk about recycling; replacing old lightbulbs; and eating local. They often miss the things that really do help. Surveys have shown this disconnect over and over.

Our radar is even off when it comes to eating meat, which some would consider to be one of our most primitive and intuitive behaviours. Grass-fed beef seems like the environmentally-friendly option. Hormone-free chickens do too. Yet intensive livestock farming in feedlots often has a lower environmental cost, despite a higher price when it comes to animal welfare.

This misfire doesn’t stop with food. A plastic bag seems a lot worse than a paper one. In fact, it’s the opposite.

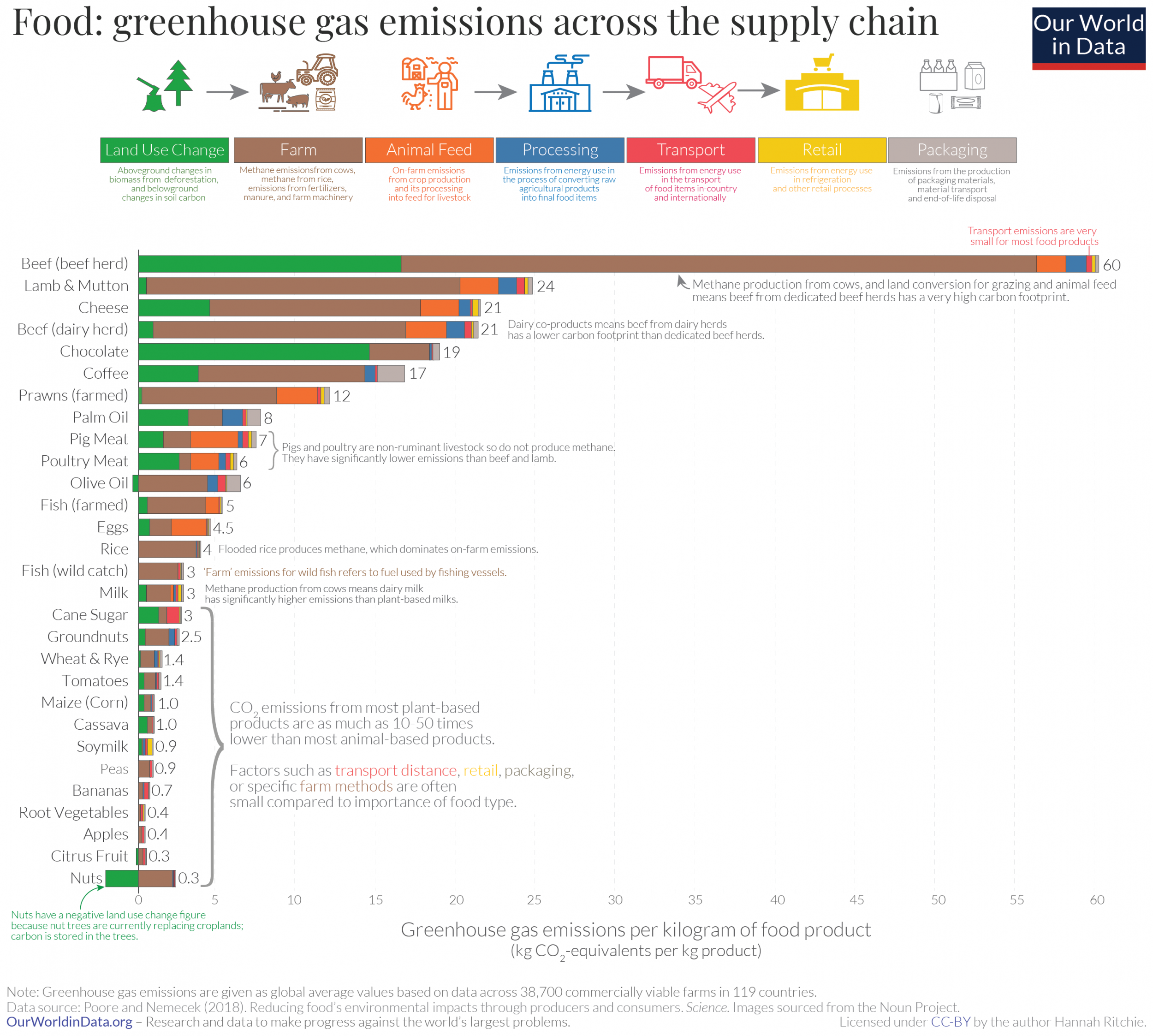

Bron: Our world in data

Bron: Our world in data

A wooden stove seems more eco-friendly than a gas heater. Many think that coal is a better option than nuclear energy, despite the latter emitting much less CO2, and being thousands of times safer. Living in the countryside seems much better than living in a city. There are few places I feel less ‘green’ than when I’m crammed against the door of the London tube. Driving to a cottage in the hills for the weekend seems infinitely more sustainable. But it’s not: dense cities are good for the climate – we can use economies of scale to reduce emissions from transport, services, and if we’re lucky we can even share heating with our neighbours.

Why, then, do we often get this so wrong? It probably comes back to the ‘natural fallacy’: things that seem more grounded in ‘natural’ properties seem better to us. Or our ‘appeal to nature’, where natural equals good, and unnatural equals bad. We’re skeptical of synthetic stuff that comes out of a factory.

It’s tempting to mock this way of thinking. We can brand it as ‘unscientific’, because, in many ways it is unscientific. I don’t need to rhyme off the countless examples of plants, viruses, and compounds that are ‘natural’ but fatal.

But ridicule has never been an effective way to drive change. And perhaps another reason I avoid this easy swipe is that I haven’t totally gotten rid of these feelings myself. I still get the instinctual pull towards ‘natural’ solutions that seem more grounded in our roots. Working against it takes repeated, and sometimes uncomfortable, effort.

Yet it’s something that we need to overcome. The fact that our intuitions are so ‘off’ is really a problem. At a time when the world needs to eat less meat we’ve seen a pushback against meat substitute products because they’re ‘processed’. When we need to be using less land for agriculture we’ve seen a recent resurgence in organic, but more land-hungry farming. When more of us need to be living in dense cities I hear more people dreaming of a romantic life in the countryside with a self-sufficient garden plot.

I’m currently writing a book about the opportunity we have to be the first generation that leaves the environment in a better state than we found it. I need to lay out the behaviours that move us forward, not backward. This is a tall order: I need to convince people of a vision that seems intuitively wrong to them. It’s hard to undo millennia of social programming.

The curious and open-minded often find delight in a surprising finding. Others are tougher to crack, especially if their identity has already become tied to a particular set of behaviours. I can try to win them over with hard facts and numbers, but that on its own is probably going to fall short. Our behaviours are rarely based on pure rationality. How we feel about them matters.

Part of the motivation for living more sustainably is feeling like you’re doing your bit. If what we ‘need’ to do is at-odds with what feels right, then that’s a problem. That means that the societal image of sustainability needs to change. Lab-grown meat, dense cities, and nuclear energy need a rebrand. These need to be some of the new emblems of a sustainable path forward.

It’s only then – when the image of ‘environmentally-friendly’ behaviours line up with the effective ones – that being a good environmentalist might stop feeling so bad.

This article was published in Works in Progress. Hannah Ritchie is Head of Research at Our World In Data. She tweets at @_HannahRitchie.

Watching me make a meal looks like an environmental travesty. I almost exclusively use the microwave. I don’t take time to savour the process: a meal that takes longer than ten minutes is one that’s not worth having. It nearly always comes from a packet. My avocados are shipped over from Mexico, and bananas transported from Angola. It’s rare that my food is produced locally. Or if it is, I don’t check the label enough to notice.

This is the opposite of what seems sustainable. The image we have in our head of the ‘environmentally-friendly meal’ is one that’s sourced from the local market; produced on an organic farm without nasty chemicals; and brought home in a paper bag, not a plastic wrapper. Forget the processed junk: it’s meat and vegetables, as fresh as they come. We set aside time to cook them properly, in the oven.

I know that my way of eating is low-carbon. I’ve spent years poring over the data. Microwaves are the most efficient way to cook. Local food is often no better than food shipped from continents away. Organic food often has a higher carbon footprint. And packaging is a tiny fraction of a food’s environmental footprint, and often lengthens its shelf-life.

Bron: Our world in data

Bron: Our world in dataYet it still feels wrong. I know I’m doing the right thing for the environment, but there’s still a part of me that feels like a traitor. I can see the confusion on peoples’ faces when they hear about some of my decisions. I feel embarrassed that people might think that I’m being a ‘bad’ environmentalist.

This problem stems from the fact that what is ‘good’ for the environment often doesn’t line up with our intuitions. Ask people about what behaviours are most effective in reducing their carbon footprint, and they talk about recycling; replacing old lightbulbs; and eating local. They often miss the things that really do help. Surveys have shown this disconnect over and over.

Our radar is even off when it comes to eating meat, which some would consider to be one of our most primitive and intuitive behaviours. Grass-fed beef seems like the environmentally-friendly option. Hormone-free chickens do too. Yet intensive livestock farming in feedlots often has a lower environmental cost, despite a higher price when it comes to animal welfare.

This misfire doesn’t stop with food. A plastic bag seems a lot worse than a paper one. In fact, it’s the opposite.

Bron: Our world in data

Bron: Our world in dataA wooden stove seems more eco-friendly than a gas heater. Many think that coal is a better option than nuclear energy, despite the latter emitting much less CO2, and being thousands of times safer. Living in the countryside seems much better than living in a city. There are few places I feel less ‘green’ than when I’m crammed against the door of the London tube. Driving to a cottage in the hills for the weekend seems infinitely more sustainable. But it’s not: dense cities are good for the climate – we can use economies of scale to reduce emissions from transport, services, and if we’re lucky we can even share heating with our neighbours.

Why, then, do we often get this so wrong? It probably comes back to the ‘natural fallacy’: things that seem more grounded in ‘natural’ properties seem better to us. Or our ‘appeal to nature’, where natural equals good, and unnatural equals bad. We’re skeptical of synthetic stuff that comes out of a factory.

It’s tempting to mock this way of thinking. We can brand it as ‘unscientific’, because, in many ways it is unscientific. I don’t need to rhyme off the countless examples of plants, viruses, and compounds that are ‘natural’ but fatal.

But ridicule has never been an effective way to drive change. And perhaps another reason I avoid this easy swipe is that I haven’t totally gotten rid of these feelings myself. I still get the instinctual pull towards ‘natural’ solutions that seem more grounded in our roots. Working against it takes repeated, and sometimes uncomfortable, effort.

Yet it’s something that we need to overcome. The fact that our intuitions are so ‘off’ is really a problem. At a time when the world needs to eat less meat we’ve seen a pushback against meat substitute products because they’re ‘processed’. When we need to be using less land for agriculture we’ve seen a recent resurgence in organic, but more land-hungry farming. When more of us need to be living in dense cities I hear more people dreaming of a romantic life in the countryside with a self-sufficient garden plot.

I’m currently writing a book about the opportunity we have to be the first generation that leaves the environment in a better state than we found it. I need to lay out the behaviours that move us forward, not backward. This is a tall order: I need to convince people of a vision that seems intuitively wrong to them. It’s hard to undo millennia of social programming.

The curious and open-minded often find delight in a surprising finding. Others are tougher to crack, especially if their identity has already become tied to a particular set of behaviours. I can try to win them over with hard facts and numbers, but that on its own is probably going to fall short. Our behaviours are rarely based on pure rationality. How we feel about them matters.

Part of the motivation for living more sustainably is feeling like you’re doing your bit. If what we ‘need’ to do is at-odds with what feels right, then that’s a problem. That means that the societal image of sustainability needs to change. Lab-grown meat, dense cities, and nuclear energy need a rebrand. These need to be some of the new emblems of a sustainable path forward.

It’s only then – when the image of ‘environmentally-friendly’ behaviours line up with the effective ones – that being a good environmentalist might stop feeling so bad.

This article was published in Works in Progress. Hannah Ritchie is Head of Research at Our World In Data. She tweets at @_HannahRitchie.

Related