If Africa is to feed its own population soon, it will have to produce much more food. The first article of this five-part series showed that agriculture in Sub-Saharan Africa can accelerate and significantly increase its output per hectare. In the second article, we showed that most African governments can promote that process much more effectively than they are currently doing, especially by improving transport infrastructure and supporting the use of fertilisers and organic matter. In this third article, we discuss what such policies could mean for SSA's food security and economic development.

For Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) to maintain its current, decreased level of self-sufficiency (80% on average), agricultural production will have to grow at least as fast as the population. This can be achieved in two ways: by accelerating growth in production per hectare, or by expanding arable land. The more successful the former, the less the latter will be needed. Consequently, rapid productivity growth can also help conserve forests and savannahs, and thereby biodiversity and climate.

If the agricultural productivity grows faster than the population, it can also, according to the World Bank, be a powerful driver of economic development2. In that case countries can afford to import less food, hence money and labour become more readily available for other sectors and in addition food becomes cheaper, allowing wages to be moderated. Such a wage moderation creates better opportunities for developing industries, especially industries focused on the African market. For an export-oriented industry, the opportunities are currently slim, because of a factor that is little known: in most SSA countries wages are significantly higher than in, say, Vietnam. In addition, broader socio-economic development is likely to help lower the currently high birth rates, which in turn can contribute to food security and prosperity in the somewhat longer term. However, higher living standards often lead to an increase in the demand for meat and dairy, and hence for feed and land, which may reduce the benefits for biodiversity and the climate.

Cheap food, as mentioned above, can also be sourced from the world market and can then equally contribute to food security, moderation of wages and hence opportunities for development of industries and the service sector. However, such imports hamper the development opportunities of domestic agriculture and agro-industry in rural areas. On top of this, a small but rapidly growing percentage of imported food is ultra-processed and unhealthy, including sugar, soft drinks and salty snacks. Such foods lead to combinations of malnutrition and obesity, sometimes even in the same individuals3.

SSA countries and the African Union could use the current food crisis as a challenge to accelerate their agricultural productivity gains. The African Development Bank has already taken a significant step with the establishment of an African Emergency Food Production Facility aimed at increasing agricultural productivity4.

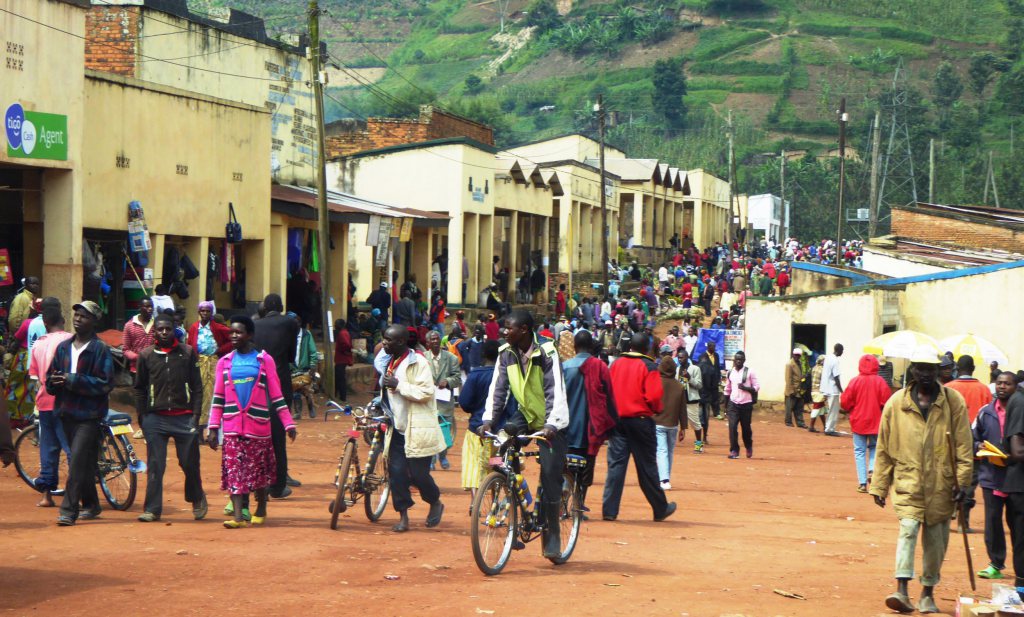

Urbanisation

Finally, we mention the role of urbanisation. This is progressing faster in SSA than in other continents. In a quarter of the African countries, more than 50% of the population already lives in cities. The champion is Gabon, with an urban population of almost 90%.

The causes of urbanisation are partly positive (urban employment), partly negative (rural poverty). The consequences are also ambivalent. The disadvantages or urban life include the poor hygiene and high infection pressure, particularly in slums5, but also the high consumption of ultra-processed food (both domestic and imported). Advantages include a higher average income, a stronger position of women and lower fertility.

In addition, the clustered labour supply in cities provides opportunities for the development of industry and services. Cheap, imported food can help depress wages and thus improve opportunities for industries. According to Wageningen professor Ewout Frankema, urbanisation could even, like agriculture, become a driving force for development. Incidentally, this is at odds with the primacy accorded to agriculture by the World Bank6 and the views of development economists such as Marcel Timmer, John Mellor and Michael Lipton, among others. The latter even wrote in 1977: if you wish for industrialisation, prepare to develop agriculture7. Indeed, the success of the Asian Tigers in the 1960s and 1970s began with an increase in agricultural productivity8. Both views contain strengths and weaknesses, but they do not apply everywhere in SSA and they still require more evidence and discussion.

Summary

This leaves the question: what can the Netherlands and Europe contribute to the desired developments? This will be the subject of the next articles, in which we also provide some building blocks for the new Africa strategy announced by the Dutch government.

Notes:

Of course, self-sufficiency is not necessary for every country, as countries can also choose, either out of necessity or by political will, to import more foodOf course, self-sufficiency is not necessary for every country, as countries can also choose, either out of necessity or by political will, to import more food. Imports from other African countries will become easier following the recent implementation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). Those countries that export energy, minerals or substantial amounts of cash crops can also easily buy food from the world market. The downside is that this does make such a country vulnerable to geopolitical or other disruptions. This was one reason for African leaders attending a conference last January in Dakar to focus on food sovereignty and resilience1.

If the agricultural productivity grows faster than the population, it can also, according to the World Bank, be a powerful driver of economic development2. In that case countries can afford to import less food, hence money and labour become more readily available for other sectors and in addition food becomes cheaper, allowing wages to be moderated. Such a wage moderation creates better opportunities for developing industries, especially industries focused on the African market. For an export-oriented industry, the opportunities are currently slim, because of a factor that is little known: in most SSA countries wages are significantly higher than in, say, Vietnam. In addition, broader socio-economic development is likely to help lower the currently high birth rates, which in turn can contribute to food security and prosperity in the somewhat longer term. However, higher living standards often lead to an increase in the demand for meat and dairy, and hence for feed and land, which may reduce the benefits for biodiversity and the climate.

Cheap food, as mentioned above, can also be sourced from the world market and can then equally contribute to food security, moderation of wages and hence opportunities for development of industries and the service sector. However, such imports hamper the development opportunities of domestic agriculture and agro-industry in rural areas. On top of this, a small but rapidly growing percentage of imported food is ultra-processed and unhealthy, including sugar, soft drinks and salty snacks. Such foods lead to combinations of malnutrition and obesity, sometimes even in the same individuals3.

SSA countries and the African Union could use the current food crisis as a challenge to accelerate their agricultural productivity gainsBesides arable farming, livestock farming also deserves a lot of attention. On the one hand, livestock farming plays an important function for agricultural development, as increasing production is easiest through mixed farms. On the other hand, given the increasing conflicts surrounding livestock farming, attention is needed especially in transition zones between regions where (nomadic) livestock farming and arable farming dominate, such as in the Sahel. There, more and more pastures are being cleared for arable farming instead of increasing the productivity of existing fields. Pastoralists deserve to be as high a political priority as are arable farmers.

SSA countries and the African Union could use the current food crisis as a challenge to accelerate their agricultural productivity gains. The African Development Bank has already taken a significant step with the establishment of an African Emergency Food Production Facility aimed at increasing agricultural productivity4.

Urbanisation

Finally, we mention the role of urbanisation. This is progressing faster in SSA than in other continents. In a quarter of the African countries, more than 50% of the population already lives in cities. The champion is Gabon, with an urban population of almost 90%.

The causes of urbanisation are partly positive (urban employment), partly negative (rural poverty). The consequences are also ambivalent. The disadvantages or urban life include the poor hygiene and high infection pressure, particularly in slums5, but also the high consumption of ultra-processed food (both domestic and imported). Advantages include a higher average income, a stronger position of women and lower fertility.

In addition, the clustered labour supply in cities provides opportunities for the development of industry and services. Cheap, imported food can help depress wages and thus improve opportunities for industries. According to Wageningen professor Ewout Frankema, urbanisation could even, like agriculture, become a driving force for development. Incidentally, this is at odds with the primacy accorded to agriculture by the World Bank6 and the views of development economists such as Marcel Timmer, John Mellor and Michael Lipton, among others. The latter even wrote in 1977: if you wish for industrialisation, prepare to develop agriculture7. Indeed, the success of the Asian Tigers in the 1960s and 1970s began with an increase in agricultural productivity8. Both views contain strengths and weaknesses, but they do not apply everywhere in SSA and they still require more evidence and discussion.

Summary

- Accelerated increases in agricultural productivity have a wide range of benefits: increased food security, increased prosperity, less need for food imports, more money and labour available for other sectors, moderation of wages and hence better opportunities for industrial development (especially industries for the African market). In addition: less clearing of forests and savannahs and hence less degradation of biodiversity and climate.

- Not every country needs to be self-sufficient in food. Importing food from the region often may offer a good alternative. Cheap food from the world market also has advantages but comes at the expense of domestic agriculture. That makes countries extra vulnerable to world market disruptions, as many of them have been experiencing since last year following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

- Agriculture can be a powerful starter motor of economic development for many countries in SSA. For other countries, the same may hold for urbanisation.

This leaves the question: what can the Netherlands and Europe contribute to the desired developments? This will be the subject of the next articles, in which we also provide some building blocks for the new Africa strategy announced by the Dutch government.

Notes:

- https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/2023/01/27/dakar_ii_declaration_food_sovereignty_and_resilience_.pdf

- World Bank, World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development.

- T. Reardon et al (2021). The processed food revolution in African food systems and the double burden of malnutrition. Global Food Security 28, 100466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2020.100466

- https://www.afdb.org/sites/default/files/news_documents/african_development_bank_ group_africa_food_emergency_production_plan_summary_copy-v2.pdf. Focus: 1) Delivering certified seeds, fertiliser and extension services to 20 million farmers, using innovation as well as internet and communications technology platforms. Supporting post-harvest management and market development. 2) Providing financing and credit guarantees for the large-scale supply of fertilizer to wholesalers and aggregators. 3) Supporting policy reform facilitating modern inputs getting to farmers, including strengthening national institutions overseeing input markets.

- SSA has by far the highest percentage of urban dwellers living in slums. https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization.

- World Bank (2008). Agriculture for Development.

- Michael Lipton (1977). Why Poor People Stay Poor: Urban Bias in World Development.

- David Henley (2015), Asia-Africa Development Divergence - A Question of Intent. Zed Books, London, and Niek Koning (2017), Food Security, Agricultural Policies and Economic Growth - Long-Term Dynamic in the Past, Present and Future, Routledge, Oxon/New York.

Henk Breman is an agrobiologist who has a long-lasting experience in research in several African countries and author of the book From fed by the world to food security – Accelerating agricultural development in Africa (2019).

Wouter van der Weijden is an environmental biologist and director of the Centre for Agriculture and Environment.

Wouter van der Weijden is an environmental biologist and director of the Centre for Agriculture and Environment.

Related