Sustainability labels are proliferating. Will there ever be a universal label that is easily understood and fools nobody? During a recent Agrifoodnetworks webinar on ALDI's choice for PlanetProof, 71% of the participants said they thought so; 29% thought a universal sustainability label to be an illusion. For the viability of a sustainability label, a focused approach and communication to consumers is crucial, explained Peter Leendertse of environmental research and consultancy CLM and Erna van der Wal of supermarket formula ALDI. Even though customers don't know what makes them trust a product, its appeal does make a difference. Once consumers discover that there are differences between standards, distrust grows. How do supermarkets and food processors deal with this phenomenon?

Back in the 1990s, Peter Leendertse, senior consultant and deputy director at CLM Research and Advisory, was the founder of a label positioned between 'organic' and its strict set of requirements and supervision, and conventional agriculture. Consumers needed 'something' that indicated that certain sustainability standards, such as consideration for the environment, were included in production or cultivation processes lacking an organic certification. That Dutch 'something' became the label 'Milieukeur', the predecessor of today's (still Dutch)On the Way to Planet Proof.

In 2016, things accelerated. Prompted by Greenpeace, which in 2016 used a naming and shaming-campaign to denounce supermarkets for doing nothing to protect bees, supermarkets wanted to develop an 'intermediate standard'. Moving to 100 percent organic was and is a commercial no go. The On the Way to Planet Proof-label, that had been developed meanwhile, certified sustainability for a number of aspects. It also included inspections and was available for various product categories.

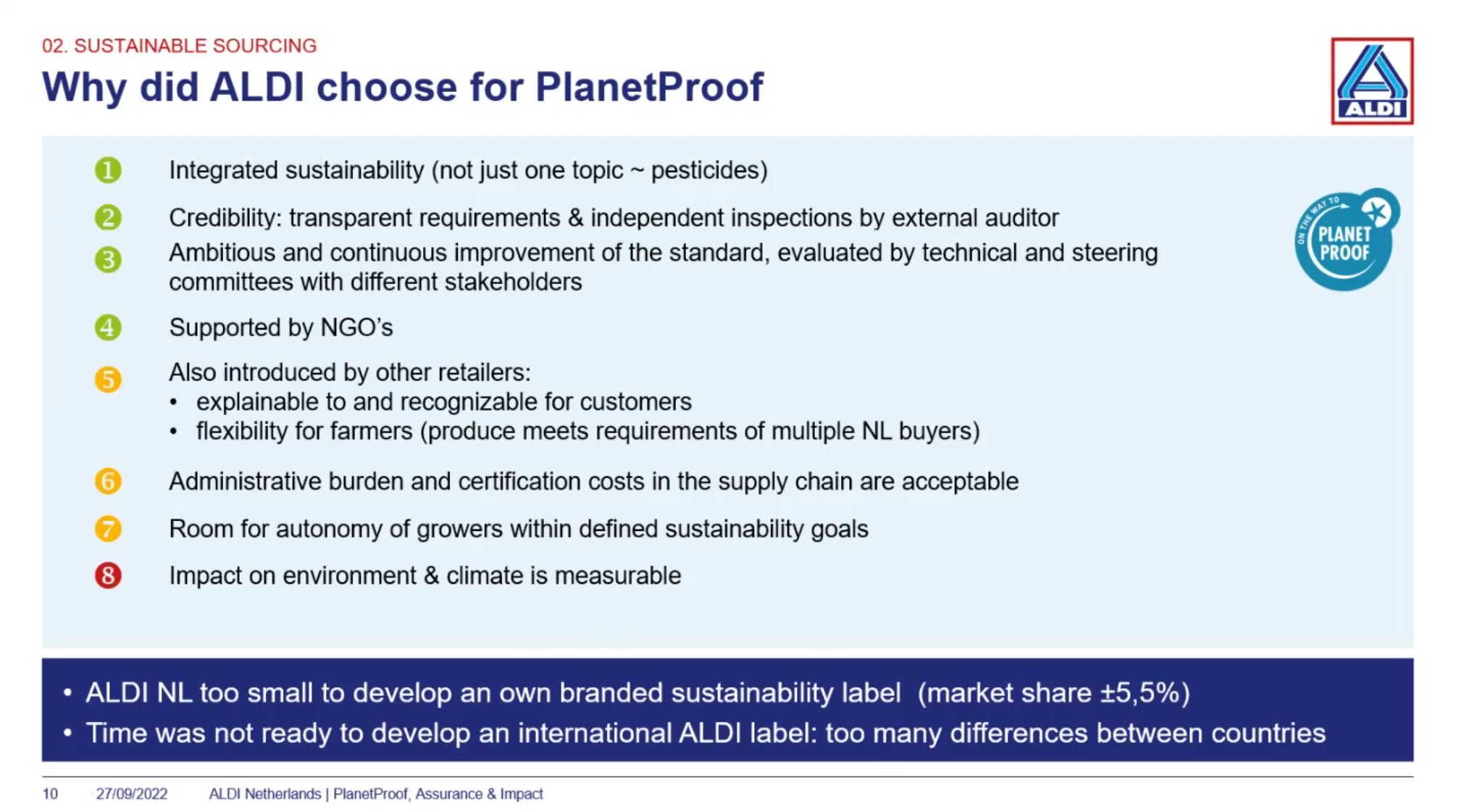

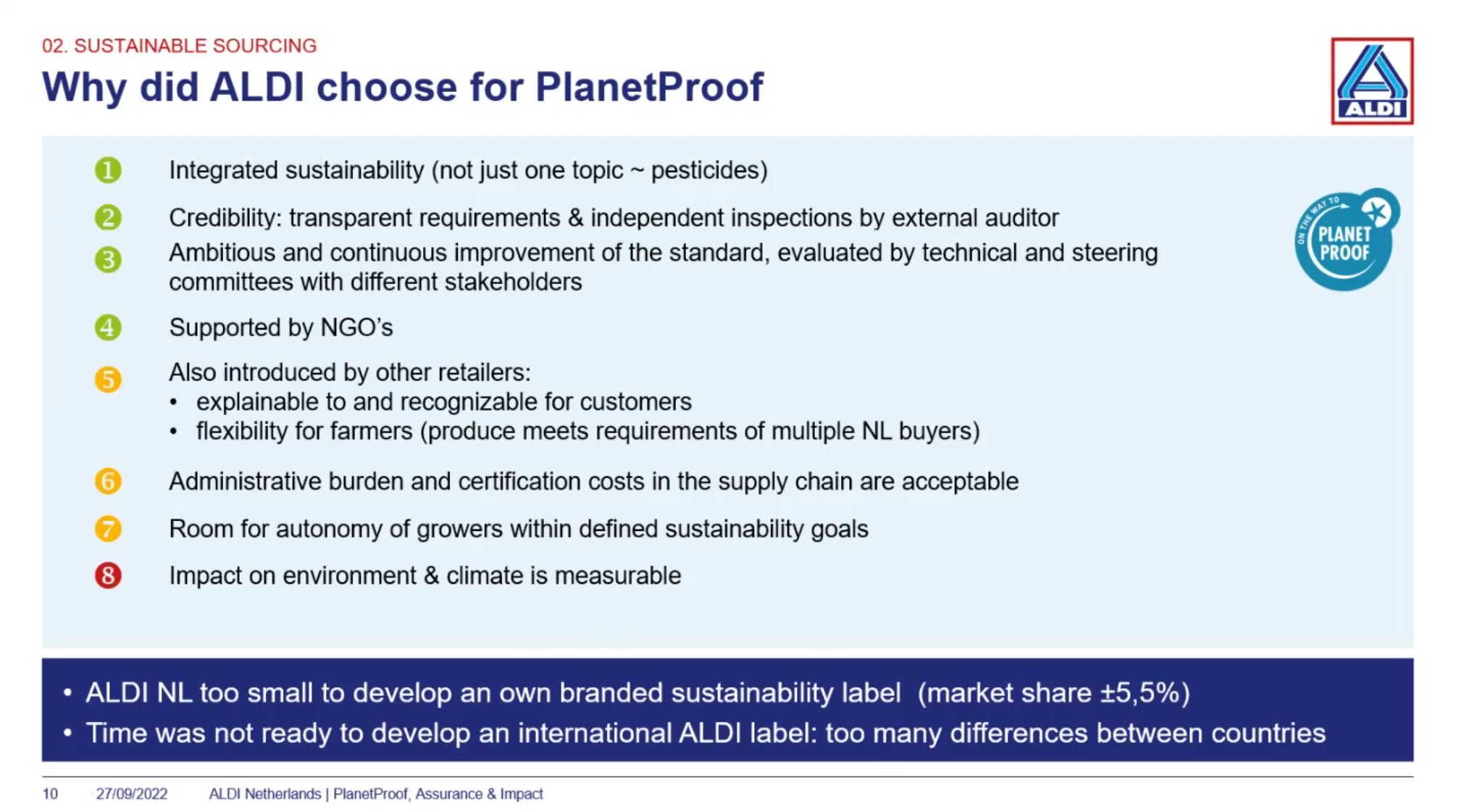

Therefore, 2016 was, for Erna van der Wal, Head of Quality Assurance & Corporate Responsibility ALDI Nord in the Netherlands, the starting point for implementation of a sustainability label. ALDI wanted only 1 label for its entire assortment. After all, unlike full-service supermarkets like Albert Heijn and Jumbo, which have, for example, different types and brands of milk, discounter ALDI offers only one in each category.

In 2017, ALDI Netherlands met with their suppliers (farmers) and collectively they made some important decisions:

How is such a label developed? Leendertse explains that for the development of the PlanetProof label, a number of 'critical performance indicators' (KPIs) had to be defined. The main input had to come from the data used by farmers in their farming operations. This included a variety of data, from CO2 emissions and pesticide use to the application of green inputs, and especially the improvement therein. The label is not called "on the way to" for no reason.

Data collection is complicated by the fact that farmers use all kinds of tools, sensors and software. Unfortunately, they don't necessarily 'talk' to each other. Furthermore, benchmarks must be defined and regularly updated to ensure progress, and the framework must remain manageable for the farmers. A further complication is that if a producer wants to comply with several standards at the same time, he will have to be able to prove his compliance one by one.

Harmonization

The last part of the webinar focused the discussion on the importance of harmonization. According to Van der Wal, it is important for ALDI Netherlands to stick with its own focal points within one harmonized framework and make a difference to customers. It turns out that consumers are not concerned what kind of label is used. However, customers do prefer products that originate 'close to home'.

ALDI is left with several challenges, says Van der Wal. Has all the data been sufficiently validated and do they reflect real-world situations? Can customers trust us enough on this and are we spending our money where it is most effective?

Questions like these direct the participants' final discussion to the underlying problem that, in the absence of a universal standard, each sustainability label looks at different aspects and effects that are considered important. However, why would those specific aspects be the most important?

For consumers, differences between their 'trusted standards' lead to confusion once they discover these vary from one to another. Therefore, companies realize that, apart from facilitating a single standard for international supplies, they will also have to work on harmonization. Consumer trust depends on simplicity and comprehensibility that need to be accurate.

In 2016, things accelerated. Prompted by Greenpeace, which in 2016 used a naming and shaming-campaign to denounce supermarkets for doing nothing to protect bees, supermarkets wanted to develop an 'intermediate standard'. Moving to 100 percent organic was and is a commercial no go. The On the Way to Planet Proof-label, that had been developed meanwhile, certified sustainability for a number of aspects. It also included inspections and was available for various product categories.

Therefore, 2016 was, for Erna van der Wal, Head of Quality Assurance & Corporate Responsibility ALDI Nord in the Netherlands, the starting point for implementation of a sustainability label. ALDI wanted only 1 label for its entire assortment. After all, unlike full-service supermarkets like Albert Heijn and Jumbo, which have, for example, different types and brands of milk, discounter ALDI offers only one in each category.

In 2017, ALDI Netherlands met with their suppliers (farmers) and collectively they made some important decisions:

- Aldi Netherlands was too small to develop its own label, but wanted an integrated sustainability approach

- It was not time for an international ALDI-wide label, but in the Netherlands first steps could be set

- the focus should not be on 1 product type, but on the sustainability of agriculture as a whole

- affiliation with other retailers/farmers was desirable because it would prevent farmers from having to deal with several different standards

It turns out that consumers are not concerned with what kind of label is used. Customers do, however, prefer products that originate 'close to home'.Based on these considerations, ALDI decided to implement the On the Way to Planet Proof-label for its fruits and vegetables, with the goal of more than 95% of the products in the stores to be PlanetProof in 2019. Fresh dairy products were added in 2019 and cheese in 2021. The target has been met by and large, and ALDI is looking at new categories, such as fresh meat.

How is such a label developed? Leendertse explains that for the development of the PlanetProof label, a number of 'critical performance indicators' (KPIs) had to be defined. The main input had to come from the data used by farmers in their farming operations. This included a variety of data, from CO2 emissions and pesticide use to the application of green inputs, and especially the improvement therein. The label is not called "on the way to" for no reason.

Data collection is complicated by the fact that farmers use all kinds of tools, sensors and software. Unfortunately, they don't necessarily 'talk' to each other. Furthermore, benchmarks must be defined and regularly updated to ensure progress, and the framework must remain manageable for the farmers. A further complication is that if a producer wants to comply with several standards at the same time, he will have to be able to prove his compliance one by one.

Harmonization

The last part of the webinar focused the discussion on the importance of harmonization. According to Van der Wal, it is important for ALDI Netherlands to stick with its own focal points within one harmonized framework and make a difference to customers. It turns out that consumers are not concerned what kind of label is used. However, customers do prefer products that originate 'close to home'.

Consumer trust depends on accurate simplicity and comprehensibilityFurthermore, consumers want to be able to recognize easily that a product has been produced sustainably, and they want to be confident that ALDI ensures this is accurate information. That is why ALDI is focusing on more extensive consumer communication (the discounter started this spring with TV commercials). In these communication efforts, the discounter can show who their farmers are and what they are doing. This kind of storytelling helps consumers gain trust. For farmers and suppliers, it is important that they are able to get support on a local (national) level with the sustainability requirements.

ALDI is left with several challenges, says Van der Wal. Has all the data been sufficiently validated and do they reflect real-world situations? Can customers trust us enough on this and are we spending our money where it is most effective?

Questions like these direct the participants' final discussion to the underlying problem that, in the absence of a universal standard, each sustainability label looks at different aspects and effects that are considered important. However, why would those specific aspects be the most important?

For consumers, differences between their 'trusted standards' lead to confusion once they discover these vary from one to another. Therefore, companies realize that, apart from facilitating a single standard for international supplies, they will also have to work on harmonization. Consumer trust depends on simplicity and comprehensibility that need to be accurate.

Related